Cambodia economic

now browsing by tag

Cambodia: EU launches procedure to temporarily suspend trade preferences

| Op-Ed: European Commission – Press release |

Comment: នីតិវិធីដកកិច្ចអនុគ្រោះពន្ធEBAនេះគឺចាប់ផ្តើមមានឥទ្ធិពលតាំងពីសារព្រមានដំបូងរបស់លោកស្រីម៉ាលស្ត្រមម្លេះពីព្រោះជាចិត្តសាស្ត្រពាណិជ្ជកម្ម ពាណិជ្ជករមានការអល់អែកក្នុងការបន្តាក់ទុននិងពង្រីកទុនរបស់ខ្លួននៅប្រទេសកម្ពុជារួចទៅហើយ។ ពាក្យពេជ្រតំណាងអោយសហគមអុឺរ៉ុបគឺអាចយកជាការបាននិងមិនមែនជាប្រជាភិថុតិដូចទំលាប់មេដឹកនាំខ្មែរបានធ្វើកន្លងមកនោះទេ។ ពាណិជ្ជករមានភាពមុឺងម៉ាត់ណាស់ចំពោះបញ្ហានេះ។ អ្វីដែលអាភ័ព្វនោះគឺលោកហ៊ុន-សែនដែលបានធ្វើនយោបាយប្រជាសាកលនិយមឬប្រជាភិថុតិជាមួយកម្មករកន្លងមក កំពុងរុញច្រានអោយកម្មករកាត់ដេរខ្មែរជិតមួយលាននាក់ធ្លាក់ខ្លួនក្រដើម្បីដោះដូរជាមួយនឹងការរក្សាអំណាចរបស់បុរសខ្លាំងកម្ពុជាតែប៉ុណ្ណោះ។ ជាការកត់សំគាល់ លោកហ៊ុន-សែនកំពុងតែស្ថិតនៅឯកោឯកាម្នាក់ឯងបន្តិចម្តងៗ។ គាត់ឯកោឯកាពីសមាជិកអ្នកស្រឡាញ់ជាតិពិតប្រាកដក្នុងជួរគណបក្សរបស់គាត់ គាត់ឯកោឯកាពីសហគមអន្តរជាតិមានសហរដ្ឋអាមេរិកជាដើម គាត់ឯកោឯកាពីប្រទេសជិតខាងរបស់កម្ពុជាមានថៃនិងវៀតណាមក៏ដូចជាសមាគមអាស៊ានជាដើម។ល។និង។ល។

Cambodia: EU launches procedure to temporarily suspend trade preferences

Brussels, 11 February 2019

The EU has today started the process that could lead to the temporary suspension of Cambodia’s preferential access to the EU market under the Everything But Arms (EBA) trade scheme. EBA preferences can be removed if beneficiary countries fail to respect core human rights and labour rights.

Launching the temporary withdrawal procedure does not entail an immediate removal of tariff preferences, which would be the option of last resort. Instead, it kicks off a period of intensive monitoring and engagement. The aim of the Commission’s action remains to improve the situation for the people on the ground.

High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Vice President of the European Commission Federica Mogherini said: “Over the last eighteen months, we have seen the deterioration of democracy, respect for human rights and the rule of law in Cambodia. In February 2018, the EU Foreign Affairs Ministers made clear how seriously the EU views these developments. In recent months, the Cambodian authorities have taken a number of positive steps, including the release of political figures, civil society activists and journalists and addressing some of the restrictions on civil society and trade union activities.However, without more conclusive action from the government, the situation on the ground calls Cambodia’s participation in the EBA scheme into question. As the European Union, we are committed to a partnership with Cambodia that delivers for the Cambodian people. Our support for democracy and human rights in the country is at the heart of this partnership.”

EU Commissioner for Trade Cecilia Malmström said: “It should be clear that today’s move is neither a final decision nor the end of the process. But the clock is now officially ticking and we need to see real action soon. We now go into a monitoring and evaluation process in which we are ready to engage fully with the Cambodian authorities and work with them to find a way forward. When we say that the EU’s trade policy is based on values, these are not just empty words. We are proud to be one of the world’s most open markets for least developed countries and the evidence shows that exporting to the EU Single Market can give a huge boost to their economies. Nevertheless, in return we ask that these countries respect certain core principles. Our engagement with the situation in Cambodia has led us to conclude that there are severe deficiencies when it comes to human rights and labour rights in Cambodia that the government needs to tackle if it wants to keep its country’s privileged access to our market.”

Following a period of enhanced engagement, including a fact-finding mission to Cambodia in July 2018 and subsequent bilateral meetings at the highest level, the Commission has concluded that there is evidence of serious and systematic violations of core human rights and labour rights in Cambodia, in particular of the rights to political participation as well as of the freedoms of assembly, expression and association. These findings add to the longstanding EU concerns about the lack of workers’ rights and disputes linked to economic land concessions in the country.

Today’s decision will be published in the EU Official Journal on 12 February, kicking off a process that aims to arrive at a situation in which Cambodia is in line with its obligations under the core UN and ILO Conventions:

– a six-month period of intensive monitoring and engagement with the Cambodian authorities;

– followed by another three-month period for the EU to produce a report based on the findings;

– after a total of twelve months, the Commission will conclude the procedure with a final decision on whether or not to withdraw tariff preferences; it is also at this stage that the Commission will decide the scope and duration of the withdrawal. Any withdrawal would come into effect after a further six-month period.

High Representative/Vice-President Mogherini and Commissioner Malmström launched the internal process to initiate this procedure on 4 October 2018. Member States gave their approval to the Commission proposal to launch the withdrawal procedure at the end of January 2019.

Background

The Everything But Arms arrangement is one arm of the EU’s Generalised Scheme of Preferences (GSP), which allows vulnerable developing countries to pay fewer or no duties on exports to the EU, giving them vital access to the EU market and contributing to their growth. The EBA scheme unilaterally grants duty-free and quota-free access to the European Union for all products (except arms and ammunition) for the world’s Least Developed Countries, as defined by the United Nations. The GSP Regulation provides that trade preferences may be suspended in case of “serious and systematic violation of principles” laid down in the human rights and labour rights Conventions listed in Annex VIII of the Regulation.

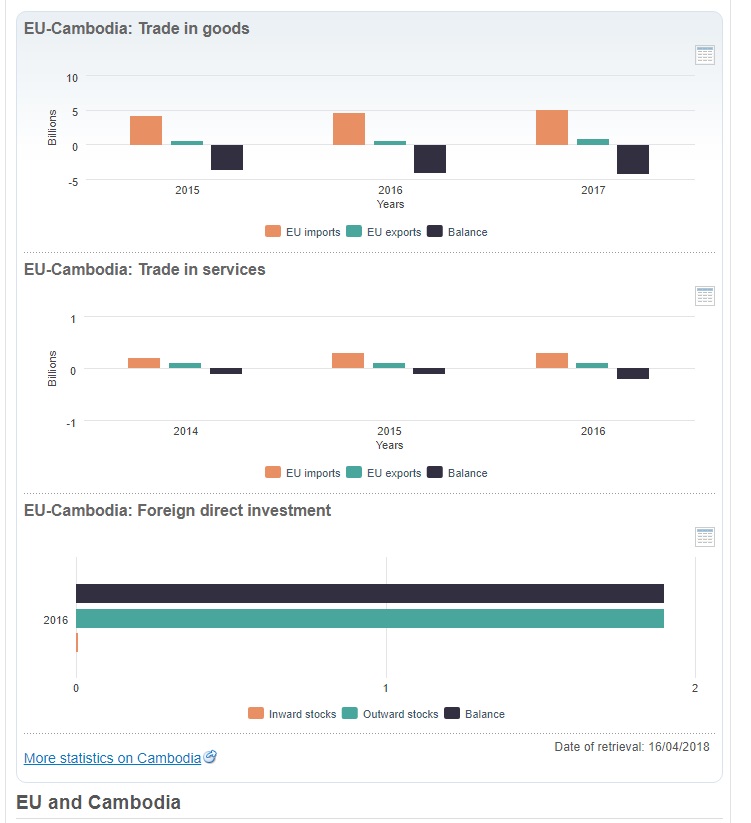

Exports of textiles and footwear, prepared foodstuffs and vegetable products (rice) and bicycles represented 97% of Cambodia’s overall exports to the EU in 2018. Out of the total exports of € 4.9bn, 99% (€ 4.8bn) were eligible to EBA preferential duties.

For More Information

MEMO: EU triggers procedure to temporarily suspend trade preferences for Cambodia

Generalised Scheme of Preferences

===========

EU starts process to hit Cambodia with trade sanctions

Op-Ed: Reuters

BRUSSELS, Feb 11 (Reuters) – The European Union started on Monday an 18-month process to end Cambodia’s preferential trade access to the bloc over its record on human and labour rights and democracy.

The European Commission, which coordinates trade policy for the 28-member EU, said that its decision would be published in the EU official journal on Feb. 12, triggering a countdown that would run until August 2020.

Read More …