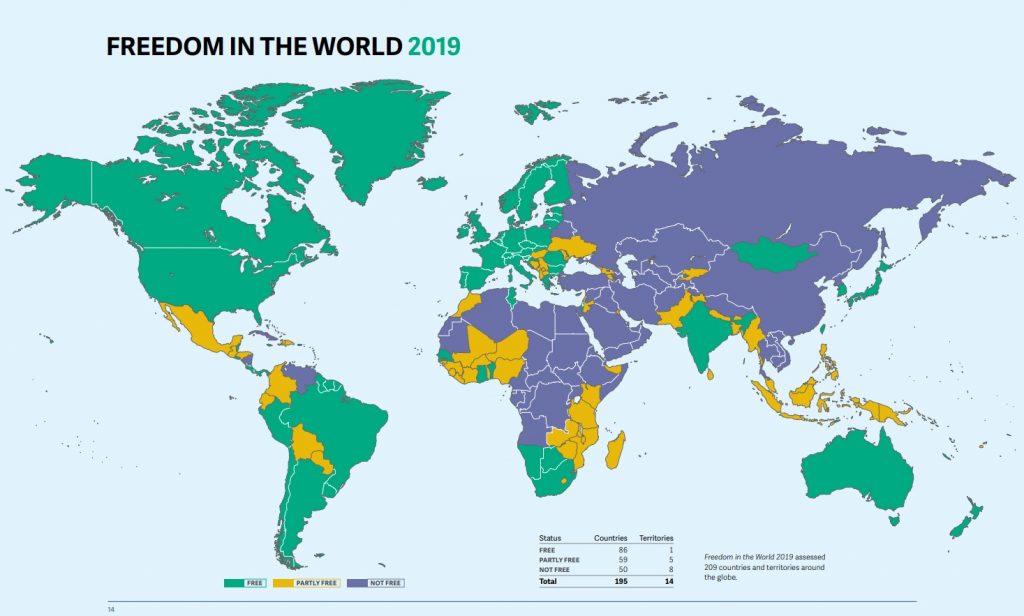

Freedom house rated Cambodia is “no free” country under Hun Sen leadership

Posted by: Leadership Skills | Posted on: February 10, 2019Cambodian prime minister Hun Sen cemented his grip on power with lopsided general elections that came after authorities dissolved the main opposition party and shuttered independent media outlets. The military and police openly campaigned for the ruling party, which won all the seats in the legislature.

នាយករដ្ឋមន្ត្រីកម្ពុជាលោកហ៊ុន-សែនចាក់គ្រឹះអំណាចរបស់គាត់តាមរយៈការបោះឆ្នោតជាតិដែលខ្វះធម្មានុរូបច្បាប់ដែលបានប្រព្រឹត្តឡើងបន្ទាប់ពីអាជ្ញាធររំលាយគណបក្សជំទាស់ដ៏សំខាន់និងបិទប្រព័ន្ធផ្សព្វផ្សាយឯករាជ្យ។ មន្ត្រីយោធានិងប៉ូលីសបើកយុទ្ធនាការគាំទ្រគណបក្សគ្រប់គ្រងអំណាចយ៉ាងចំហរដែលគណបក្សនេះបានឈ្នះកៅអីសភាទាំងអស់តែម្តង។

Op-Ed: Key Developments by Freedom House Report 2019

Read more news on VOA in Khmer Language, and VOA in English

KEY DEVELOPMENTS IN 2018:

- The CPP won every seat in the lower house, the National Assembly, in July elections. The polls were held amid a period of repression that began in earnest in 2017, and saw the banning of the main opposition party, opposition leaders jailed or forced into exile, and remaining major independent media outlets reined in or closed. The CPP also dominated elections for the upper house, or Senate, held in February, taking every elected seat.

- The Phnom Penh Post, regarded by many observers as the last remaining independent media outlet in Cambodia, was taken over by a Malaysian businessman with links to Hun Sen.

- A Cambodian court sentenced an Australian filmmaker to six years in jail on charges of espionage. He had been arrested after denouncing rights abuses and filming political rallies.

- In November, the UN-assisted court known as the Khmer Rouge Tribunal found Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan, two surviving leaders of the Khmer Rouge, guilty of genocide and crimes against humanity. The verdict for the first time legally defined the Khmer Rouge’s crimes as genocide.

OVERVIEW:

Cambodia’s political system has been dominated by Prime Minister Hun Sen and his Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) for more than three decades. The country has conducted semicompetitive elections in the past, but the 2018 polls were held in a severely repressive environment that offered voters no meaningful choice. The main opposition party was banned, opposition leaders were in jail or exiled, and independent media and civil society outlets were curtailed. The CPP won every seat in the lower house for the first time since the end of the Cambodian Civil War, as well as every elected seat in the upper house in indirect elections held earlier in the year. Political Rights and Civil Liberties:

POLITICAL RIGHTS: 6 / 40 (–4)

A. ELECTORAL PROCESS: 1 / 12 (–3)

A1. Was the current head of government or other chief national authority elected through free and fair elections? 0 / 4 (–1)

King Norodom Sihamoni is chief of state, but has little political power. The prime minister is head of government, and is appointed by the monarch from among the majority coalition or party in parliament following legislative elections. Hun Sen first became prime minister in 1985. He was nominated most recently after 2018 National Assembly polls, which offered voters no meaningful choice. Most international observation groups were not present due to the highly restrictive nature of the contest.

Score Change: The score declined from 1 to 0 because the incumbent prime minister was unanimously confirmed for another term after parliamentary elections that offered voters no meaningful choice.

A2. Were the current national legislative representatives elected through free and fair elections? 0 / 4 (–1)

The bicameral parliament consists of the 62-seat Senate and the 125-seat National Assembly. Members of parliament and local councilors indirectly elect 58 senators, and the king and National Assembly each appoint 2. Senators serve six-year terms, while National Assembly members are directly elected to five-year terms.

In 2018, the CPP won every seat in both chambers in elections that were considered neither free nor fair by established international observers, which declined to monitor them. In the months before the polls, the Supreme Court had banned the main opposition Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP) and jailed many of its members, and closed media outlets and intimidated journalists to the extent that there was almost no independent reporting on the campaign or the polls. Several small, obscure new “opposition parties” ran candidates in the lower house elections, though many of the parties were widely believed to have been manufactured to suggest multiparty competition. Following calls for an election boycott by former CNRP leaders, Hun Sen repeatedly warned that people who did not vote in the election could be punished. The election was condemned by many democracies. The United States responded by imposing targeted sanctions on Cambodian leaders, while the EU threatened to roll back a preferential trade agreement.

Score Change: The score declined from 1 to 0 because the parliamentary elections took place in a highly repressive environment that offered voters no meaningful choice, and produced a one-party legislature.

A3. Are the electoral laws and framework fair, and are they implemented impartially by the relevant election management bodies? 1 / 4 (–1)

In 2015, Cambodia passed two new election laws that permit security forces to take part in campaigns, punish parties that boycott parliament, and mandate a shorter campaign period of 21 days. The laws have been broadly enforced.

Voting is tied to a citizen’s permanent resident status in a village, township, or urban district, and this status cannot be changed easily. In 2017, an amendment to the electoral law banned political parties from association with anyone convicted of a criminal offense.

The National Election Committee (NEC) was reformed in 2013, but the CPP has since asserted complete control over its nine seats. Criminal charges were brought against the body’s one independent member in 2016, who was then jailed and removed from the body. The four NEC members affiliated with the CNRP resigned following the party’s 2017 dissolution. In 2018, the NEC sought to aid the CPP’s campaign by threatening to prosecute any figures that urged an election boycott, and informing voters via text message that criticism of the CPP was prohibited.

Score Change: The score declined from 2 to 1 because the election commission, controlled by the ruling party since the ouster of independent and opposition members, participated in the government’s efforts to control the outcome of the parliamentary elections.

B. POLITICAL PLURALISM AND PARTICIPATION: 2 / 16 (–1)

B1. Do the people have the right to organize in different political parties or other competitive political groupings of their choice, and is the system free of undue obstacles to the rise and fall of these competing parties or groupings? 0 / 4 (–1)

Following the 2018 elections, Cambodia is a de facto one-party state. The main opposition CNRP was banned and its leaders have been charged with crimes, while other prominent party figures have fled the country. Although several small opposition parties contested the 2018 July lower house elections, none won seats. All of the smaller parties were permitted to run by the CPP-controlled National Election Committee, and both domestic and international observers widely questioned their authenticity.

Score Change: The score declined from 1 to 0 because the only significant opposition party remained banned and persecuted even as multiple parties of dubious authenticity were allowed to register for parliamentary elections, creating an illusion of competition.

B2. Is there a realistic opportunity for the opposition to increase its support or gain power through elections? 0 / 4

The political opposition has been quashed, with the CNRP banned and its leaders facing criminal charges. The high rate of spoiled ballots in the 2018 lower house election—8.6 percent of all votes, according to the NEC—suggested strong popular discontent with the lack of choice, especially given that Hun Sen had repeatedly warned Cambodians not to spoil ballots. Elections for the upper house earlier in the year were similarly structured so that the CPP had no real opposition. There were widespread reports of voters being bullied and intimidated before the July lower house elections into casting a vote for the CPP.

After the elections, amid increasing international scrutiny, Hun Sen and the CPP modestly eased pressure on the opposition. In August, the king pardoned 14 CNRP members who had been jailed for “insurrection.” CNRP co-leader Kem Sokha was released on bail in September after spending a year in solitary confinement on treason charges, though he still faced significant restrictions on his movement. Late in 2018, the government initiated legislation that could allow bans on political activity for some opposition figures to be lifted.

CNRP co-leader Sam Rainsy has remained abroad; he was convicted of defamation in 2017 and faces a number of other legal cases in Cambodia, and risks imprisonment if he returns. Many other prominent CNRP figures remain in exile. At year’s end, the opposition appeared ready to split, with supporters of Rainsy and Kem Sokha seemingly parting ways.

B3. Are the people’s political choices free from domination by the military, foreign powers, religious hierarchies, economic oligarchies, or any other powerful group that is not democratically accountable? 1 / 4

The ruling party is not democratically accountable, and top leaders, especially Hun Sen, use the police and armed forces as a tool of repression. The military has stood firmly behind Hun Sen and his violent threats, and his crackdown on opposition. Hun Sen has built a personal bodyguard unit in the armed forces that he reportedly uses to harass and abuse CPP opponents.

Before the 2018 lower house elections, Human Rights Watch reported that the security forces were illegally campaigning for the CPP. Additionally, several top military commanders won seats in the lower house as CPP legislators. One, General Pol Saroeun, then vacated his seat to become a senior minister in the new government.

B4. Do various segments of the population (including ethnic, religious, gender, LGBT, and other relevant groups) have full political rights and electoral opportunities? 1 / 4

Ethnic Vietnamese are regularly excluded from the political process and scapegoated by both parties. Women make up 15 percent of the National Assembly, but their interests, like those of all citizens, are not well represented.

C. FUNCTIONING OF GOVERNMENT: 3 / 12

C1. Do the freely elected head of government and national legislative representatives determine the policies of the government? 1 / 4

Hun Sen has increasingly centralized power, and figures outside of his close circle have little impact on policymaking. Some reports suggest he is preparing to eventually hand power to his son, Hun Manet, who has deep ties throughout the armed forces. In September, Hun Manet was promoted to commander of the armed forces.

C2. Are safeguards against official corruption strong and effective? 1 / 4

Anticorruption laws are poorly enforced, and corruption remains a serious challenge in Cambodia. A 2016 Global Witness report suggested that Hun Sen’s family had amassed wealth totaling between $500 million and $1 billion, claims that the prime minister and his family deny. Corruption is rampant in public procurement, tax administration, customs administration, and other state processes, and bribes are frequently required in dealings with various government departments.

C3. Does the government operate with openness and transparency? 1 / 4

Nepotism and patronage undermine the functioning of a transparent bureaucratic system. A draft access to information law was made public in January 2018, though domestic observers expressed concern that upon implementation it would be ignored or misused. The law was pending at year’s end.

CIVIL LIBERTIES: 20 / 60

D. FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION AND BELIEF: 8 / 16

D1. Are there free and independent media? 1 / 4

The government uses lawsuits, criminal prosecutions, massive tax bills, and occasionally violent attacks as means of intimidation against the media. There are private print and broadcast outlets, but many are owned and operated by the CPP.

Starting in 2017 the government engaged in an intense crackdown on independent media, and these efforts continued throughout 2018. In 2017, the independent Cambodia Daily closed under pressure from the government regarding its tax bills. In 2018, the Phnom Penh Post, known for its independent and investigative reporting, was sold to a Malaysian investor with links to Hun Sen, and many of its editors and reporters quit or were fired following the sale. In addition, many other local media outlets were intimidated into closing or, in the run-up to the July lower house elections, becoming government mouthpieces. Before the lower house elections, the election commission released a code of conduct for journalists that mandated fines of as much as $7,500 for using “their own ideas to make conclusions” or publishing news deemed to “affect political and social stability” or cause “confusion and loss of confidence” regarding the election.

Two Radio Free Asia journalists arrested in 2017 on charges of espionage still face trial in Cambodia. In August 2018, an Australian filmmaker was sentenced to six years in jail for espionage, after creating footage about rights abuses and public rallies. Late in 2018, Hun Sen publicly promised to ease pressure on independent media, as well as on civil society more generally and on the political opposition; his government offered to allow the Cambodia Daily and Radio Free Asia to reopen in Cambodia, although it remained unclear whether they would do so.

D2. Are individuals free to practice and express their religious faith or nonbelief in public and private? 3 / 4

The majority of Cambodians are Theravada Buddhists and can practice their faith freely, but societal discrimination against religious and ethnic minorities persists.

D3. Is there academic freedom, and is the educational system free from extensive political indoctrination? 2 / 4

Teachers and students practice self-censorship regarding discussions about Cambodian politics and history. Criticism of the prime minister and his family is often punished.

D4. Are individuals free to express their personal views on political or other sensitive topics without fear of surveillance or retribution? 2 / 4

The state generally does not intervene in people’s private discussions, though open criticism of the prime minister can result in reprisals. In 2018, however, Hun Sen and other government leaders warned ahead of the lower house election that criticism of the government would be punished severely. Additionally, an order issued before the election required internet service providers (ISPs) to install software necessary to monitor, filter, and block “illegal” online content, including social media accounts.

Earlier, in February, an amendment to the criminal code introduced a new lèse-majestéoffense that made it illegal to defame, insult, or threaten the king. The law carries a sentence of between one and five years in jail, and a fine of 2 to 10 million riel (about $500 to $2,500).

E. ASSOCIATIONAL AND ORGANIZATIONAL RIGHTS: 3 / 12

E1. Is there freedom of assembly? 1 / 4

Authorities are openly hostile to free assembly. The shooting deaths of five postelection protesters by security forces in 2014 discouraged opposition demonstrations, as have continued government assertions that dissent will not be tolerated. The few small opposition parties that did contest the lower house elections had few or no events. In March, a land dispute in Kratie over the activities of a rubber plantation resulted in police firing on protestors and possibly killing eight people, although reports of the incident vary.

E2. Is there freedom for nongovernmental organizations, particularly those that are engaged in human rights– and governance-related work? 1 / 4

Activists and civil society groups dedicated to justice and human rights face increasing state harassment. Prominent activist Kem Ley was murdered in broad daylight in 2016. In January 2018, three activists involved with planning his funeral were charged with embezzlement, though charges against one of them were later dropped. A number of other activists faced legal harassment during the year, including some with the Cambodian Human Rights and Development Association (ADHOC). The National Democratic Institute, a US-based nongovernmental organization (NGO), was forced to shut its Cambodia operations in 2017.

A variety of less overtly political groups are able to operate.

E3. Is there freedom for trade unions and similar professional or labor organizations? 1 / 4

Cambodia has a small number of independent trade unions, and workers have the right to strike, but many face retribution for doing so. A 2016 law on trade unions imposed restrictions such as excessive requirements for union formation.

F. RULE OF LAW: 3 / 16

F1. Is there an independent judiciary? 0 / 4

The judiciary is marred by corruption and a lack of independence. Judges have facilitated the government’s ability to pursue charges against a broad range of opposition politicians, and played a central role in keeping Kem Sokha in a remote jail, without bail, despite significant health problems, for nearly a year. He was finally freed on bail in September 2018, but with severe restrictions on his movement.

F2. Does due process prevail in civil and criminal matters? 1 / 4

Due process rights are poorly upheld in Cambodia. Abuse by law enforcement officers and judges, including illegal detention, remains extremely common. Sham trials are frequent, while elites generally enjoy impunity. When lawyers or others criticize judges, they often face retribution.

F3. Is there protection from the illegitimate use of physical force and freedom from war and insurgencies? 1 / 4

Cambodians live in an environment of tight repression and fear. The torture of suspects and prisoners is frequent. The security forces are regularly accused of using excessive force against detained suspects.

The ongoing work of the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC), established to try the leaders of the former Khmer Rouge regime, has brought convictions for crimes against humanity, homicide, torture, and religious persecution. In November 2018, the tribunal found Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan, two surviving leaders of the Khmer Rouge, guilty of genocide and crimes against humanity. They both received life sentences; both had already been sentenced to life in prison for past convictions of crimes against humanity. The 2018 convictions marked the first time the Khmer Rouge crimes were legally defined as genocide.

While others closer to the regime have faced allegations of involvement in these crimes, there is little indication the Hun Sen government will support additional prosecutions. It appears likely that there will be no further cases brought to the ECCC.

F4. Do laws, policies, and practices guarantee equal treatment of various segments of the population? 1 / 4

Minorities, especially those of Vietnamese descent, often face legal and societal discrimination. Officials and opposition leaders, including Sam Rainsy, have demonized minorities publicly.

The Cambodian government frequently refuses to grant refugee protections to Montagnards fleeing Vietnam, where they face persecution by the Vietnamese government.

While same-sex relationships are not criminalized, LGBT individuals have no legal protections from discrimination.

G. PERSONAL AUTONOMY AND INDIVIDUAL RIGHTS: 6 / 16

G1. Do individuals enjoy freedom of movement, including the ability to change their place of residence, employment, or education? 2 / 4

The constitution guarantees the rights to freedom of travel and movement, and the government generally respects these rights in practice. However, restrictions do occur, notably when the government tries to prevent activists from traveling around the country.

G2. Are individuals able to exercise the right to own property and establish private businesses without undue interference from state or nonstate actors? 1 / 4

Land and property rights are regularly abused for the sake of private development projects. Over the past several years, hundreds of thousands of people have been forcibly removed from their homes, with little or no compensation, to make room for commercial plantations, mine operations, factories, and high-end residential developments.

G3. Do individuals enjoy personal social freedoms, including choice of marriage partner and size of family, protection from domestic violence, and control over appearance? 2 / 4

The government does not frequently repress personal social freedoms, but women suffer widespread social discrimination. Rape and violence against women are common.

G4. Do individuals enjoy equality of opportunity and freedom from economic exploitation? 1 / 4

Equality of opportunity is severely limited in Cambodia, where a small elite controls most of the economy. Labor conditions can be harsh, sometimes sparking protests. Sex and labor trafficking remains a significant problem, and while the government’s program to combat it is inadequate, the US State Department has said the Cambodian government has increased its antitrafficking efforts.

Comments are Closed