Archives

now browsing by author

ខ្ញុំជាទំពាំងក្នុងរដូវប្រឡងបាក់ឌុប

ខ្ញុំជាទំពាំង (អានក្នុង pdf)

១. ខ្ញុំជាទំពាំងក្នុងសង្គមបើក បាក់ឌុបកក្រើកប្រឡងយកជាប់

ខ្ញុំនៅតែឆ្ងល់កូនខ្មែររៀបរាប់ នេះជាទំលាប់ឬជាយ៉ាងណា? ។

២. ១២ឆ្នាំខ្ញុំប្រឹងរៀនរហូត តែជួនរបូត២ថ្ងៃសីហា

តាមពិតខ្ញុំមិន(មែន)ជាកូនទេវតា(fixed mindset) ខ្ញុំជាអ្នកស្នេហាសិក្សាខ្មីឃ្មាត(growth mindset)។

៣. ប្រឡងពីរថ្ងៃដូចចាប់បង្ខំ ហើយកុំបន្លំថាជាការស្រឡាញ់ជាតិ

មិនគួរអួតអាងអោយធំហួសមាឌ អង្គរកេរជាតិកើតដោយព្បាយាម ។

៤. អប់រំស្រុកខ្មែរត្រូវតែកែរទំរង់ ប្រឡងបាក់ឌុបគួរលប់ចេញភ្លាម

ដើរទាន់ពិភពលោកកូនខ្មែរទារទាម ទំពាំងមិនស្ងៀមចង់រីកធំជាក់ស្តែង ។

សេង សុភ័ណ

មើលកូនបណ្តើរហ្វេសប៊ុកបណ្តើរ

ម៉ោង១០ព្រឹក ថ្ងៃទី១៧ ខែសីហា ឆ្នាំ២០១៩

Posted in Culture, Economics, Education, Leadership, Politics | Comments Off on ខ្ញុំជាទំពាំងក្នុងរដូវប្រឡងបាក់ឌុប

Cambodia’s opposition faces renewed crackdown amid China shift

As he spoke, his eyes filled with tears.

The family said they were told by prison officials that Rorn had a seizure, hit his head and died – but they dispute the story. According to Tita, Rorn had no history of epilepsy and his injuries did not seem consistent with a seizure.

After the funeral, Tita fled the village. He said police had come looking for him at his home on two occasions.

“I am scared but I want to tell the truth and I want justice,” he said.

Cambodia’s opposition faces renewed crackdown amid China shift

Op-Ed: Al Jazeera

With senior leaders jailed or exiled, local and regional supporters of opposition report attacks and harassment.by Andrew Nachemson & Yon Sineat19 May 2019

![CNRP leader Kem Sokha greets supporters on the last day of campaigning ahead of local elections in 2017. He was detained a few months later and remains under house arrest [File: Heng Sinith/AP Photo]](https://www.aljazeera.com/mritems/imagecache/mbdxxlarge/mritems/Images/2019/5/16/cc6243e3b91d4a32a59f740fbc2ebd0d_18.jpg)

MORE ON CAMBODIA

- China ‘to help’ Cambodia if EU implements trade sanctions3 weeks ago

- Gateless: A Story of Child Sex Abuse in Cambodia’s Templeslast month

- Calls grow for investigation over missing Cambodian land activistlast month

- Cambodian court issues arrest warrants for top opposition leaders2 months ago

Phnom Penh, Cambodia – Nol Puthearith was a security guard at the headquarters of the Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP), and continued to watch over the building in the Cambodian capital even after the main opposition party itself was forcibly dissolved by the government of Prime Minister Hun Sen.

Chinese investment brings casinos to Cambodia (2:34)

Last month, he was attacked by a group of strangers.

“They beat me until I was unconscious,” said Puthearith, who has supported the opposition and acted as a bodyguard for party leaders since the late 1990s. “I have no idea who they are and I can’t identify them.”

A week after the April 13 attack in Phnom Penh, another opposition member named Tith Rorn was taken to a police station in Kampong Cham province for questioning over a crime that had taken place more than a decade ago.

Cambodian court issues arrest warrants for top opposition leaders

While not directly related, the two events are part of what some observers see as a pattern of ongoing abuse and intimidation against political opponents of Hun Sen, exacerbated by a recent threat by the European Union to cancel its preferential Everything But Arms (EBA) trade agreement with Cambodia over its human rights record.

Hun Sen has accused the EU of holding Cambodia hostage and warned that he would renew his crackdown on the opposition if Europe did not relent.

Lee Morgenbesser, author of Behind the Facade: Elections under Authoritarianism in Southeast Asia, said that while the CNRP is officially disbanded, the government still fears its influence because its supporters have been driven underground.

“Hun Sen’s government has eliminated the threat of the CNRP at the national level, but it has much work to do at the local level,” he explained. “The problem for Hun Sen now is identifying who to repress, how to repress them and when to repress them.”

The CNRP’s leader Kem Sokha remains under house arrest after he was detained at the end of 2017 and accused of treason.

The party itself, which came a close second in the 2013 national elections and in the 2017 local polls, was dissolved two years ago on spurious allegations of attempted revolution aided by the United States. The move ensured that Hun Sen’s Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) secured every one of the 125 seats in the National Assembly in last year’s election.

Although there was a relaxation of political repression after the polls and many political prisoners were released, including 14 members of the CNRP, the attacks on opposition supporters have now resumed.

CNRP member Kong Mas, who supported cancelling the EBA, was arrested for incitement in January.

Tith Rorn, a supporter of Cambodia’s opposition CNRP who was detained over a fight that happened 13 years ago and died in mysterious circumstances in prison three days later [Al Jazeera]

Beatings, assaults

At least three individuals, including Puthearith, have been assaulted in cases the party claims are politically motivated since March.

Rorn, the CNRP coordinator, was arrested on April 15 over a fight with a pro-government activist that took place 13 years ago, well beyond the statute of limitations. He later died in prison.READ MORE

Trick or real? CNRP split over Cambodia move to ease politics ban

After the altercation, Rorn fled to Anlong Veng near the Thai border but came home from time to time. He had been living in the village for about a year when the police came for him.

“On the second day of Khmer New Year at 7:30 in the morning, police came and said they needed to take him for questioning,” his father, Eam Tita, a provincial coordinator for the CNRP in Kampong Cham, told Al Jazeera from an undisclosed location.

“After they took him for questioning, he never came back and three days later police told my neighbour that my son had died.”

As he spoke, his eyes filled with tears.

The family said they were told by prison officials that Rorn had a seizure, hit his head and died – but they dispute the story. According to Tita, Rorn had no history of epilepsy and his injuries did not seem consistent with a seizure.

“There were bruises all over his body like he had been beaten and his neck was broken,” Tita said. The family was unable to get a doctor to do an official autopsy, because doctors in the area were too scared to get involved.

After the funeral, Tita fled the village. He said police had come looking for him at his home on two occasions.

“I am scared but I want to tell the truth and I want justice,” he said.

Popular opposition figure Sin Rozeth takes a selfie with a supporter after being interrogated for more than four hours by a provincial court in Battambang [Andrew Nachemson/Al Jazeera]

Strengthening grip

On May 10, Asean Parliamentarians for Human Rights (APHR), a group of MPs from around Southeast Asia, called for an independent investigation into Rorn’s death. In a statement, the group urged the Cambodian government to stop targeting members of the opposition.

“The continued attacks on the opposition shows that the government has no interest in meaningful dialogue, but is only concerned with strengthening its own grip on power,” said Charles Santiago, APHR chairman and a Malaysian MP, said in the statement.

Last week, the US State Department also released a statement expressing concern and calling for an investigation, as well as for the release of Kem Sokha.

The United Nations Special Rapporteur, Rhona Smith, has also expressed worry, noting “few tangible improvements” in the political environment.

“I remain concerned that pressure on former members of the dissolved Cambodia National Rescue Party continue unabated,” she said in a press conference at the end of a fact-finding mission on May 9.

Puthearith, the security guard, fled to Thailand after he was attacked, but he says colleagues informed him that police have come looking for him three times. He fears he might be permanently detained or worse.

“I’m very concerned for my safety, that’s why I fled Cambodia. What happened to me is politically motivated because I didn’t know those people and I also don’t have any conflict with anyone,” Puthearith said.

Smith: ‘I remain concerned that pressure on former members of the dissolved Cambodia National Rescue Party continue unabated’ [Heng Sinith/AP Photo]

‘Seek refugee status, not a problem’

Read More …The injustice of Cambodian justice

Police are underpaid and short-staffed, while Cambodia’s patronage-based bureaucracy means that people tend to be promoted based on alliances, not competency or integrity.

According to the National Police, 2,969 crimes were committed last year, up from 2,817 in 2017. The number stands in contrast to the nation’s bulging prison population, however.

In November, Interior Minister Sar Kheng revealed that there were 31,008 inmates in Cambodia’s 28 prisons, of which almost 72% were being held in pre-trial detention.

That means there are roughly 190 prisoners per every 100,000 people, a bigger proportion than in most other Southeast Asian nations, and higher as a percentage than even authoritarian China.

The prison population has ballooned in recent years after the government launched in 2017 an anti-drug crackdown, similar in tone but not atrocity to the one Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte has championed. As a result, the number of inmates rose by 30% in 2017 alone, mostly for drug-related offenses.

CRIME MAY 17, 2019

Op-Ed: Asia Time

Cambodian police man a barricade outside a prison in Trapaing Phlong in Tbong Khmum province on September 11, 2017. Photo: AFP / Stringer

The injustice of Cambodian justice

The government aims to appear tough on crime, seen in a bulging prison population, but ranked second worst worldwide on a recent rule of law index

ByDAVID HUTT, PHNOM PENH

Ask any Cambodian about the key issues facing their country and chances are that crime will be near the top of the list. But on nearly all counts, the country’s justice system is failing.

According to the National Police, 2,969 crimes were committed last year, up from 2,817 in 2017. The number stands in contrast to the nation’s bulging prison population, however.

In November, Interior Minister Sar Kheng revealed that there were 31,008 inmates in Cambodia’s 28 prisons, of which almost 72% were being held in pre-trial detention.

That means there are roughly 190 prisoners per every 100,000 people, a bigger proportion than in most other Southeast Asian nations, and higher as a percentage than even authoritarian China.

The prison population has ballooned in recent years after the government launched in 2017 an anti-drug crackdown, similar in tone but not atrocity to the one Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte has championed. As a result, the number of inmates rose by 30% in 2017 alone, mostly for drug-related offenses.

The problem is bigger than drugs, though. The Cambodia Socio-Economic Survey 2016, carried out by the Ministry of Planning’s National Institute of Statistics, found that 5% of surveyed households were victims of property crimes, such as theft and burglary.

But anecdotal evidence suggests that almost all petty crime goes unreported to the police. A 2014 United National Development Program report on sexual violence even found that the vast majority of women and men rape victims never report the crime.

“People do not trust law implementation and the justice system in Cambodia,” said Noan Sereiboth, a political blogger and frequent contributor to the youth-centered group Politikoffee.

In recent months, the government has tried to be seen as tackling higher-level crimes.

Read More …HIDING IN PLAIN SIGHT: CHINESE EXPANSION IN SOUTHEAST ASIA

HIDING IN PLAIN SIGHT: CHINESE EXPANSION IN SOUTHEAST ASIA

Op-Ed: War on the Rocks

CHARLES EDELMAY 9, 2019 COMMENTARY

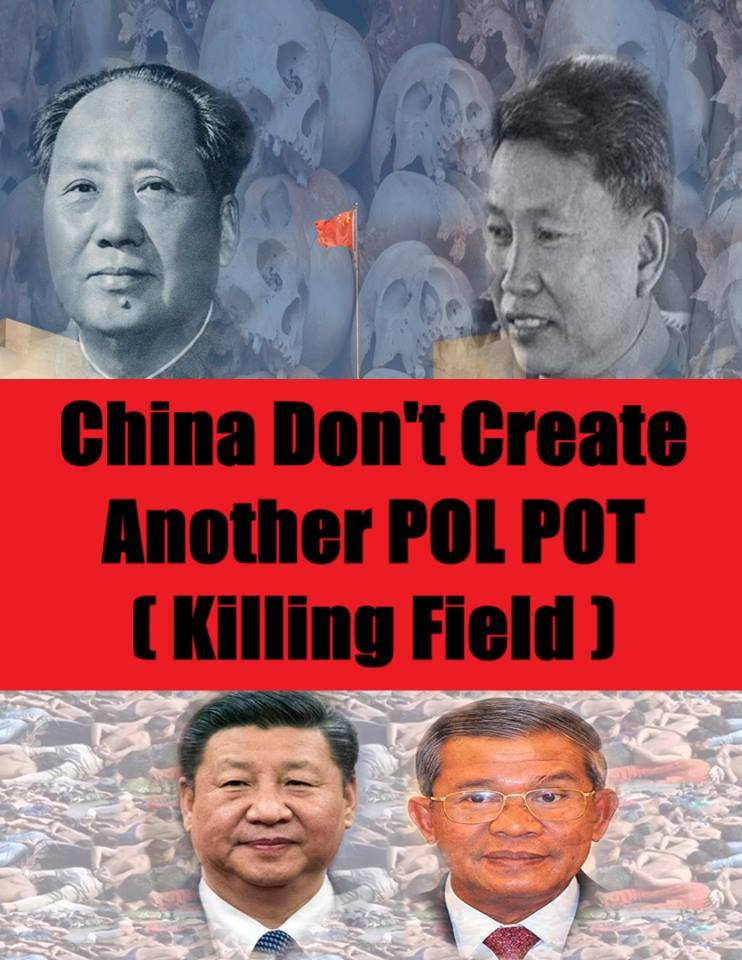

Beijing’s geopolitical moves continue to obfuscate its larger designs, surprise observers, and render the United States and its allies reactive. The prospect of a Chinese naval base in Cambodia offers a case in point.

This issue — seemingly obscure and inconsequential to many observers — made the news in late 2018 when American Vice President Mike Pence raised it in a letter to Cambodia’s increasingly authoritarianleader, Hun Sen. Subsequently, Hun Sen dismissed media reports that China sought a naval base in Cambodia as “fake news.” In repeated denials, he proclaimed that Cambodia’s constitution prohibits any foreign country from setting up military bases within the country’s sovereign territory.

Recent satellite imagery depicting an airport runway in Cambodia’s remote Koh Kong province. Its length is similar to those built on the Spratly Islands in the South China Sea and it is long enough to support Chinese military reconnaissance, fighter, and bomber aircraft. Source: EO Browser.

And yet, questions remain. Recent commercial satellite imagery shows that Union Development Group, a Chinese-owned construction firm, has been rushing to complete a runway in Cambodia’s remote Koh Kong province on the southwestern coast. It appears long enough to support military aircraft and matches the length of the runways built on the Spratly Islands in the South China Sea to support military reconnaissance, fighter and bomber aircraft. Moreover, given the amount of political and economic support Hun Sen has received from Beijing, his independence seems increasingly doubtful.

However, these accusations and denials prevent a meaningful discussion of what the establishment of such a base would mean and what an appropriate response to such an eventuality would look like. They also obscure the question of why Beijing would seek to build a military base in Cambodia.

For Beijing, the strategic dividends of acquiring a military base in southeast Asia are numerous: a more favorable operational environment in the waters ringing southeast Asia, a military perimeter ringing and potentially enclosing mainland southeast Asia, and potentially easier and less restricted access to the Indian Ocean. These benefits are not all of equal value to Chinese strategists, nor does China need any of them immediately. But the logic of Chinese expansion suggests that sooner or later, Beijing will need such a military outpost in southeast Asia, and Hun Sen’s Cambodia presents especially fertile geographic and political soil.

While Hun Sen currently denies that he would allow the rotational presence of the Chinese military or a more permanent Chinese military base on Cambodian territory, strategy often deals in the realm of the possible. Proactively dealing with this challenge requires understanding the Chinese template for developing military bases, thinking through the strategic effects of such a base in Cambodia, and developing options to forestall such a development.

The Chinese Template

Forming a picture of what a Chinese military outpost in Cambodia could look like and how quickly one could become operational is not an act of wild speculation. Chinese efforts elsewhere provide evidence of a simple template. In the South China Sea, in Djibouti, and in other locations in the Indian and Pacific Oceans, Beijing has followed a similar pattern in which denial precedes further action and helps to veil the full extent of Beijing’s aims.

The Chinese template for construction of new military basing was on full display in the South China Sea, where Beijing pursued the quick buildup and rapid militarization of facilities in the Spratly Islands. Chinese officials denied that plans existed for base construction even as Chinese fisherman and private construction companies began to undertake such efforts. Once base construction was underway, Chinese officials claimed such actions were undertaken for humanitarian purposes and continually promised they would not militarize the South China Sea. Once militarization of these facilities was complete, Beijing again shifted its explanations, noting that the military bases were purely defensive in nature. Finally, the Chinese military began building hangars and infrastructure required to deploy fighter jets and other military aircraft to these islands, just as they installed anti-ship cruise missiles, surface-to-air missiles, and military jamming equipment.

Read More …Posted in Economics, Education, Leadership, Politics, Researches, Social | Comments Off on HIDING IN PLAIN SIGHT: CHINESE EXPANSION IN SOUTHEAST ASIA