According to a draft of the deal between Phnom Penh and Beijing, China would obtain a 30-year lease on the port, as well as a permit to station troops and storing weaponry. Two piers would be newly constructed, one for Cambodian and one for Chinese use. Chinese military personnel would be allowed to carry Cambodian passports, and Cambodians at the base would be required to get official permission from China to enter the Chinese section at the base.

យោងតាមពង្រាយឯកសារដោះដូររវាងក្រុងភ្នំពេញនិងប៉េកាំង ចិននឹងជួលកំពង់ផែរយៈពេល៣០ឆ្នាំ ក៏ដូចជាការអនុញ្ញាតអោយឈរជើងទ័ពនិងស្តុកគ្រឿងសព្វាវុធ។ ផែខ្នាតតូចពីរនឹងត្រូវកសាងឡើង មួយសម្រាប់ខ្មែរនិងមួយទៀតសម្រាប់ចិនប្រើប្រាស់។ បុគ្គលិកកងទ័ពចិននឹងត្រូវអនុញ្ញាតអោយកាន់លិខិតឆ្លងដែនខ្មែរ ហើយនៅមូលដ្ឋាននោះ ប្រជាពលរដ្ឋខ្មែរត្រូវសុំការអនុញ្ញាតពីភាគីចិនគ្រប់ពេលបើចង់ចូលទៅក្នុងមូលដ្ឋានរបស់ចិននោះ។

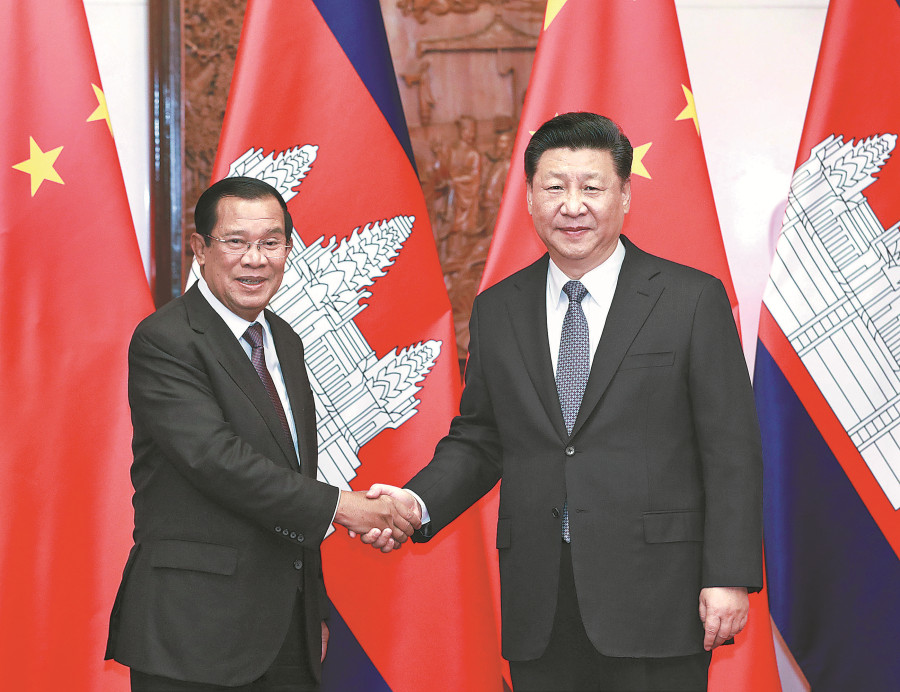

Chinese naval base in Cambodia

Op-Ed: by Hannah Elten , October 6, 2019

The undisclosed military pact between China and Cambodia forms another significant example of China pursuing dual-use infrastructure projects in the Asia-Pacific – while simultaneously denying the existence of such projects. Moreover, Hun Sen’s denial of the deal demonstrates that the Cambodian government, once viewed by Western countries as a potential ally in the region, is growing ever closer to China. Lastly, Chinese access to Ream base marks another step towards a looming rivalry with India in the Pacific region.

Cambodia and China have reportedly signed a secret deal allowing Chinese military troops access to the Ream Naval Base on the Gulf of Thailand. While both Cambodia and China have denied such an agreement, recent statements made by US military officials stationed in the Asia-Pacific leave little doubt about the integrity of the report.

Developments and Denial

Cambodian officials, including Ministry of Defense spokesman General Chum Sutheat, were swift in their rejection of the suggestion that Beijing is allowed to establish a military presence in Cambodia. However, suspicions have long circulated the Dara Sakor resort, a $3.8 billion investment project entirely financed and built by the Chinese Union Development Group (UDG). The project is located near both the run down Ream Naval Base and the coastal town of Sihanoukville.

Several points indicate the veracity of the WSJ report: Around 70 km away from Ream, UDG is also constructing Dara Sakor airport, which is due to open next year and will contain a runway longer than the one at Phnom Penh airport, raising concerns that it is ultimately envisioned also to serve aircrafts of the Chinese Air Force. At Ream itself, satellite images show that an area inside the base has been recently cleared and a bridge at the entrance is being repaired, potentially in preparation for construction work.

According to a draft of the deal between Phnom Penh and Beijing, China would obtain a 30-year lease on the port, as well as a permit to station troops and storing weaponry. Two piers would be newly constructed, one for Cambodian and one for Chinese use. Chinese military personnel would be allowed to carry Cambodian passports, and Cambodians at the base would be required to get official permission from China to enter the Chinese section at the base.

Same, same – but different

The implementation of the alleged agreement seems to follow the rules of a playbook Beijing has previously used.

In the past, China had frequently denied plans for maritime infrastructure abroad, even when construction was already underway, such as in the case of its outpost in Djibouti and the creation of artificial islands in the South China Sea. Chinese scholars and political analysts do not use the term “base”, instead of naming facilities “strategic support points”, pointing out their commercial purpose and operation via state-owned companies (such as UDG). Yet, their dual-use potential is palpable. While they are unlikely to be capable of sustaining primary combat operations, they could almost certainly provide logistical support, such as fuel, to passing naval ships, long distances away from Chinese territory.

The Chinese-Cambodian agreement appears to be more agreeable towards China than similar agreements it has concluded in the wider region. It also reflects how dependent Hun Sen’s government has become in Beijing. Cambodia, although still the recipient of large amounts of development aid from Western countries such as the US and the EU, has increasingly sidelined its relations with these countries in favour of proximity to Beijing – most likely because its loans are coming with no strings attached with regards to human rights and functioning democratic institutions. Over the past two years alone, the Cambodian government has accepted more than $600 million in loans as part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

Broader geopolitical implications

On a full geopolitical scale, Chinese access to Ream has the potential to accelerate growing tensions with India in the Pacific region. Itself pursuing a deep-water port at Sambang, Indonesia, at the entrance to the Malacca Strait, India might see the advantages of its presence there reduced if China encroaches on the Strait via Cambodia, without having to rely on ships stationed at Hainan island overly.

Continue reading