For sincere condolence, love and shared responsibility of Cambodian nation: special collection of news outlets regarding Somdech Ta King Norodom Sihanouk

Cambodia’s Mercurial Former King, Norodom Sihanouk, Dies at 89

.jpg) |

| Cambodia’s former King Norodom Sihanouk greets his subjects at the annual crop-planting ceremony outside the royal palace in Phnom Penh on April 30, 2002 (Chor Sokunthea / Files / Reuters) |

|

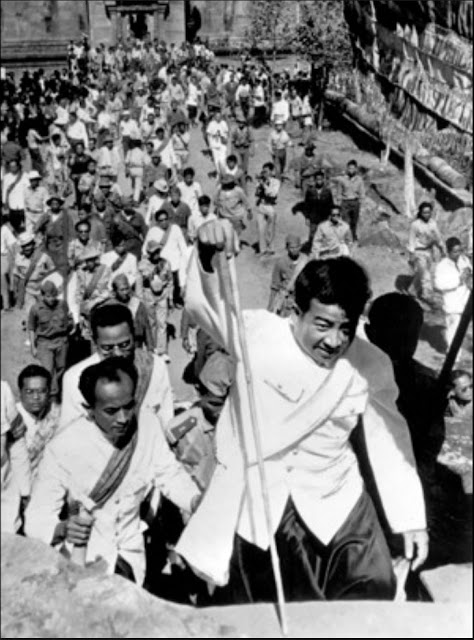

| Cambodia’s former King Norodom Sihanouk, pictured in July 1941 (AP) |

In the end, he couldn’t script a happy ending for Cambodia.

=======

Former Cambodian King Norodom Sihanouk dies at 89

- Sihanouk was monarch for more than 60 years

- He died in Beijing after suffering from various diseases

- He abdicated the throne in 2004 and his son became king

(CNN) — Former Cambodian King Norodom Sihanouk, who was monarch for more than 60 years until his abdication in 2004, died early Monday in Beijing at the age of 89, state news reported.

Sihanouk died of natural causes after having been treated by Chinese doctors for years for various forms of cancer, diabetes and hypertension, China’s state-run Xinhua news agency reported, citing Cambodian Deputy Prime Minister Nhik Bun Chhay.

The “royal government” will bring the late king’s body back to his homeland for a traditional funeral, according to Cambodia’s official AKP news agency. Xinhua reported that Sihanouk’s son, King Norodom Sihamoni, will fly to Beijing later Monday to receive his father’s body for burial.

Health problems led Sihanouk to announce his abdication in October 2004 while he was in Beijing for treatment, according to the king’s official website.

A panel elected Sihamoni as the new king. Cambodia’s National Assembly then decided to give Sihanouk the title of King Father, allowing him the same privileges he has as the reigning monarch, according to his website.

Sihanouk saw Cambodia go from French rule to independence, then to the brutal Khmer Rouge regime and the guerrilla war that followed its toppling. He then watched his country develop into the constitutional monarchy it is today.

He came from a royal lineage, but it was France that placed Sihanouk on the throne in 1941, according to the foreign ministry of Australia, which has played a key role in Cambodia’s transition toward peace.

The king dissolved the nation’s parliament in 1953, which helped bring about Cambodia’s independence.

Two years later, he abdicated the throne to his father but remained active as Cambodia’s prime minister. In 1960, he became the South Asian nation’s head of state following his father’s death.

In the 1960s, amid a region simmering with conflicts such as the Vietnam War, Cambodia soon became home to a number of North Vietnamese training camps. That prompted U.S. air strikes on those camps in 1969.

The following year, U.S.-backed Gen. Lon Nol declared a coup d’etat while the king was on an official visit to the Soviet Union and abolished the monarchy. The king went into exile in China and led a resistance movement, while the Khmer Rouge gradually gained strength.

The Khmer Rouge, led by Pol Pot, rose to power in April 1975 and began a period of mass killings, public executions and torture centers. While no one knows for certain how many people were killed by the Khmer Rouge, experts estimated 1.7 million fatalities — or at least a fifth of Cambodia’s population.

Sihanouk himself lost five children and 14 grandchildren at the hands of the Khmer Rouge.

Sihanouk was allowed to return to the country in 1976 but was confined to the royal palace until Pol Pot was overthrown three years later. He was away from Cambodia from 1979 to 1991.

The king subsequently became president of the new republic, but it wasn’t until 1993 — when Cambodia held its first parliamentary elections — that the king’s powers were restored and Cambodia became a constitutional monarchy.

Elizabeth Becker, the author of “When the War Was Over: Cambodia and the Khmer Rouge Revolution,” told CNN after the king abdicated in 2004 that Sihanouk was “larger than life” and brought both good and bad to his country.

He tried to bring Cambodia into the modern world and protect it from its neighbors, but he brought about divisions in the process, she said.

“He threw his prestige and politics behind the Khmer Rouge when they started the rebellion and it was his name that helped convince a lot of peasants to go along with the Khmer Rouge,” Becker told CNN.

“Then later, after the Vietnamese invasion, he continued to help the Khmer Rouge at the United Nations with political prestige, so his is a very checkered legacy.”

=============

King a changing constant

|

| Returned to the throne … Norodom Sihanouk in in 1973. |

October 17, 2012

Telegraph, London

Cambodians mourn Sihanouk, their King Father

Cambodia’s Former King Leaves Mixed Legacy

|

| The Cambodian king and his entourage outside the palace that Kim Il-sung built for him at Changsuwon, south of Pyongyang, in 1981. |

Remembering the life of ‘Monseigneur Papa’ Sihanouk

17/10/2012

Jacques Bekaert is a former Bangkok Post writer

Bangkok Post

“This is my pride. You can accuse me of everything you want, but never of having stolen one penny from my people.”

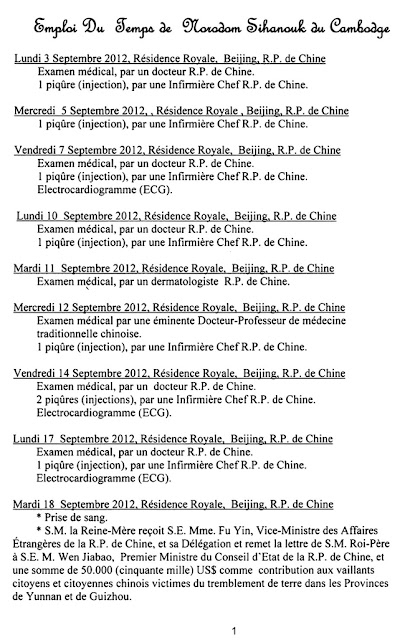

King Father Communicated Through His Website Until the Very End

|

| Schedule of Norodom Sihanouk of Cambodia (Posted on www.NorodomSihanouk.info) |

By Kate Bartlett- October 16, 2012

The Cambodia Daily

Ban expresses deep condolences to Cambodia following death of former monarch

UN News Centre

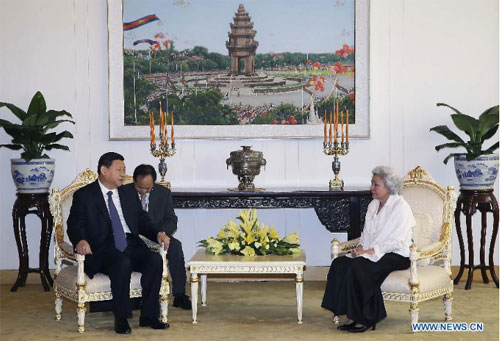

Hu Sends Condolences over Sihanouk’s Death

.jpg) |

| Hu Jintao (L) and Sihanouk (R) |

2012-10-15 Xinhua

Bidding Lea Heuy To Cambodia’s Controversial King

|

| Sihanouk in North Korea |

By Traci Tong ⋅ October 15, 2012

PRI’s The World (USA)

Magistad said Sihanouk was “charming and highly entertaining” and he often held four hour news conferences where he would read poetry. She said the former king saw himself as a Shakespearean character — someone who was larger than life at a time when Southeast Asian Politics really mattered.”“In his spare time, when he should have been governing the country in the 1960s, he would make films with a North Korean film crew because Kim Il Sung was one of his good friends, and he would write love songs, and he would play the saxophone and then he would execute political opponents and then he would make films of the executions and show them in theaters around the country so other people think about opposing him.”

Death of His Majesty King Father Norodom Sihanouk of Cambodia

Press Statement

Victoria Nuland

Department Spokesperson, Office of the Spokesperson

Washington, DC

October 15, 2012

The Bloodied Legacy of Cambodia’s Chameleon King

|

| Then-princess Monique, then-prince Sihanouk and Ieng Sary in 1973. |

October 15, 2012

By MARK MCDONALD

International Herald Tribune (Paris, France)

“By allying himself with the Khmer Rouge and urging his countrymen to join,Sihanouk condemned his people to damnation”

King Father on Preah Vihear issue

Thursday, 10 July 2008

Unofficial Translation from French

Written by The Phnom Penh Post

a/. The construction (10th and 11th centuries) of Preah Vihear by two successive Khmer Kings and is a purely Khmer work.

b/. The mountain and the temple of Preah Vihear could be found, during the 10th and 11th centuries, “very much in the interior” of Kampuchea, in the Khmer Empire, of which the borders extended for hundreds of kilometers, to the north, the east and west, much further than the current Cambodian borders with Thailand and Laos.

As a consequence, the mountain and the Preah Vihear temple could be found not on the Cambodia-Siam (Thai) border but “deep in the interior” of the Kingdom (of the Khmer Empire) and the “main entrance” of Preah Vihear “looked” not towards Siam (Thailand) but to Kampuchea.

c/. The International Court in the Hague, which in 1962, rendered justice to Cambodia, did not ignore all this, and let me, once again, offer them a respectful and admiring homage.

d/. Thanks to Khmer Sovereignty and the Khmer empire (Angkorian in particular) , present day Thailand is very rich in Angkorian style Khmer temples and monuments.

[It is] absolutely wrong and gives proof to the meanness, which, in Thailand, causes to Cambodia and its people undeserved and anachronistic troubles concerning the temple of Preah Vihear, instead of devoting ourselves to the harmonious and fruitful development of our friendship and our (authentic) brotherhood (Thai-Cambodian).

(signed) Norodom Sihanouk

King Father Norodom Sihanouk Dies at 89

By Michelle Vachon – October 15, 2012

The Cambodia Daily

Cambodia’s former King Norodom Sihanouk dies at 89

By SOPHENG CHEANG

Associated Press – 10/15/2012

Norodom Sihanouk and China: a lifelong alliance

Tuesday, October 16, 2012

AFP

OBITUARY: Sihanouk, Cambodian king during decades of tumult dies

October 15, 2012

Deutsche Presse Agentur

Photos : EPA

Obituary: Norodom Sihanouk, former king of Cambodia Norodom Sihanouk was vital force for unity in Cambodia

BBC News

Khmer Rouge deal

Though he cajoled and joked his way through these talks – Sihanouk occasionally brought his poodle to the negotiations – his performance was judged by many to be a triumph of diplomacy.

Norodom Sihanouk’s official biographer pays tribute

Norodom Sihanouk was a passionate film-maker, actor, musician.

15 October 2012

ABC Radio Australia

A look back at the life and times of Norodom Sihanouk

The former King of Cambodia, Norodom Sihanouk, has died at the age of 89.

15 October 2012

ABC Radio Australia

Norodom Sihanouk, Cambodia’s leader through decades of upheaval, dies in China at age 89

Oct 14, 2012

Sopheng Cheang, The Associated Press

Sihanouk was a ruthless politician, talented dilettante and tireless playboy, caught up in endless, almost childlike enthusiasms.

.jpg)

.jpg)

+07.jpg)

+01.jpg)

+02.jpg)

+03.jpg)

+04.jpg)

+05.jpg)

+06.jpg)

+07.jpg)

+08.jpg)

+09.jpg)

+10.jpg)

+11.jpg)

+02.jpg)

.jpg)