បញ្ហាកោះគុជ ប្រវត្តិ បដិវាទកម្ម ឆន្ទះនយោបាយ និងអនាគត

ប្រវត្តិ

អាណានិគមបារាំងបានដេីរតួនាទីយ៉ាងសំខាន់ក្នុងការវាសវែងនិងកំណត់ព្រំដែនកម្ពុជាបច្ចុប្បន្នក្នុងនាមបារាំងជាអាណាព្យាបាល១៨៦៣ដល់ឆ្នាំ១៩៥៤ ហេីយពេលកម្ពុជាទទួលបានឯករាជ្យ១១ វិច្ឆិកា ១៩៥៣ ព្រំដែននេះបានក្លាយជាព្រំដែនកម្ពុជាតំកល់នៅអង្គការសហប្រជាជាតិរហូតឈានចូលយុគកាលបច្ចុប្បន្ន។ កោះគុជ(pearl island) ខុសពីកោះត្រល់(Phuqoc Island) ត្រង់សន្ធិសញ្ញាព្រំដែនមួួយជាការកំណត់រវាងប្រទេស ហេីយមួួយទៀតជារដ្ឋបាលក្រោមអាណានិគមបារំាងមានកម្ពុជា វៀតណាម និង ឡាវ។

បដិវាទកម្ម

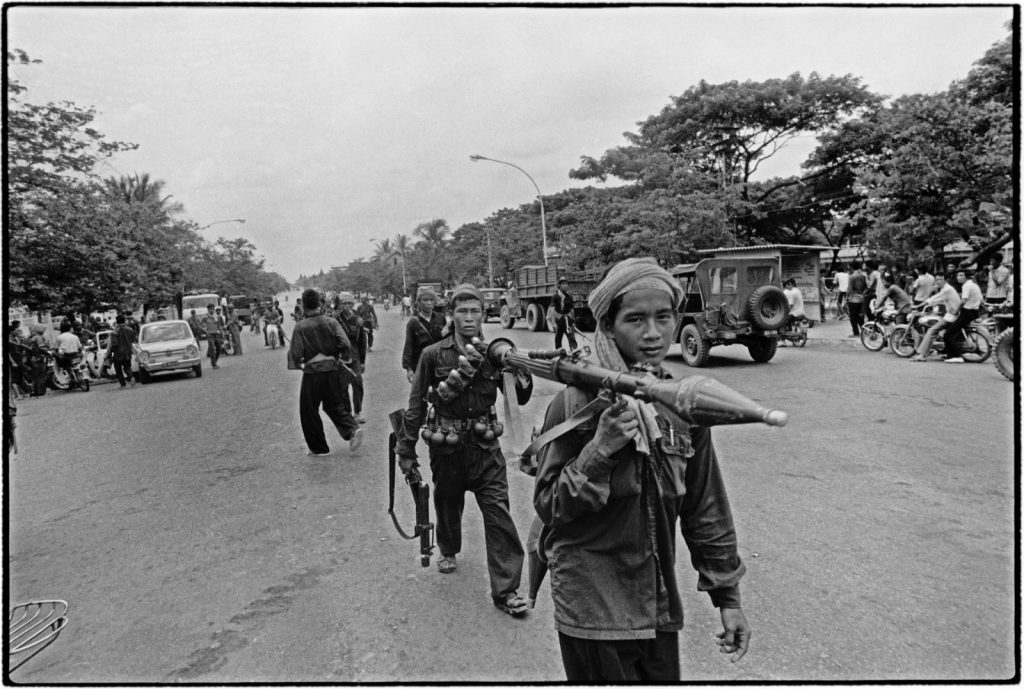

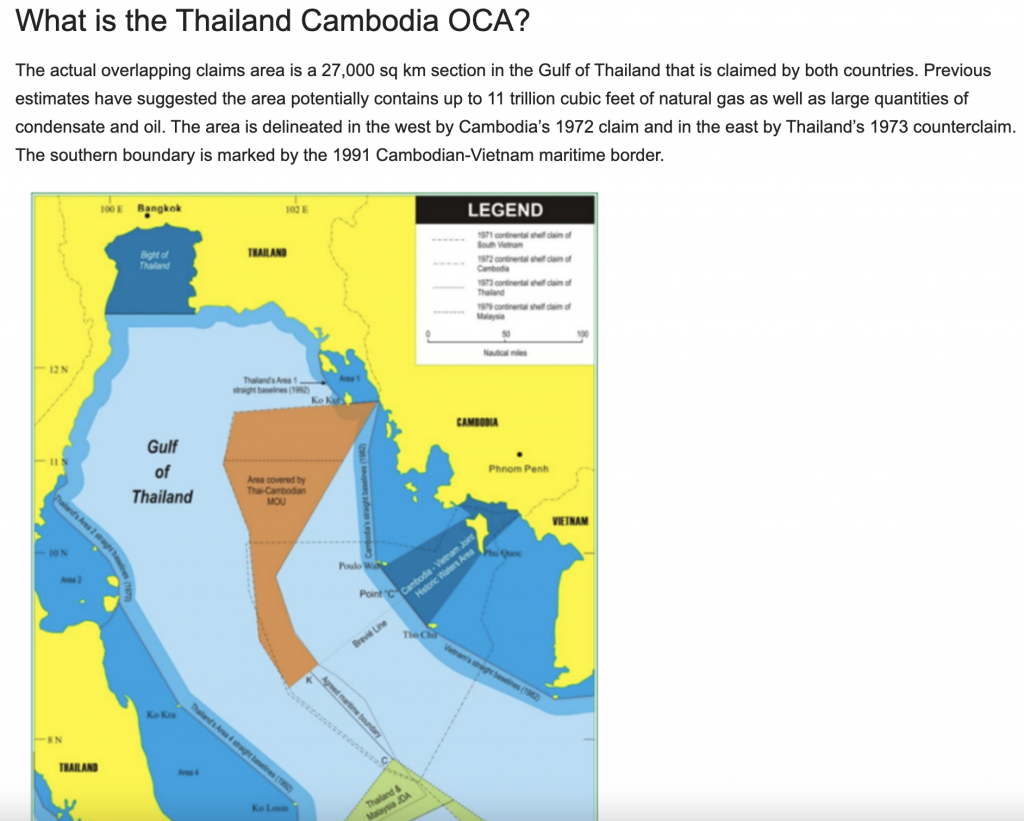

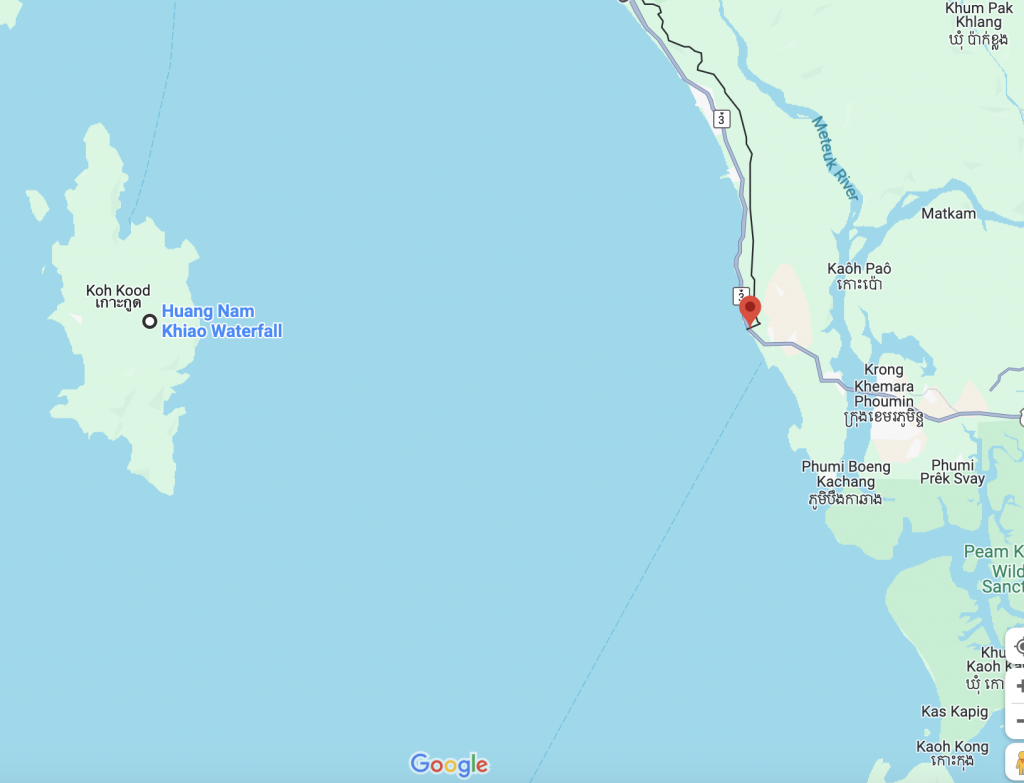

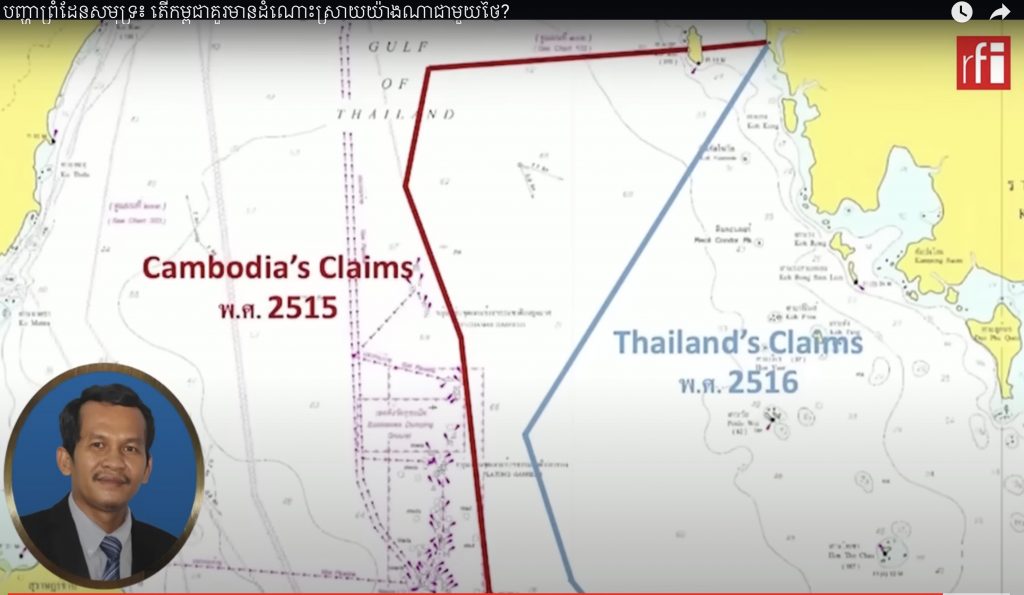

ក្រោយចាញ់ក្តីប្រាសាទព្រះវិហារជាថ្មី១១ វិច្ឆិកា ២០១៣ ក្រោយទីក្រុងឡាអេកាត់ក្តីអោយខ្មែរឈ្នះនៅថ្ងៃ១៥ មិថុនា ១៩៦២ ថៃបានសំរុកអភិវឌ្ឍន៍កោះគុជអោយក្លាយជាតំបន់ទេសចរណ៍ កសាងហេដ្ឋារចនាសម្ព័ន្ធ និងអោយពលរដ្ឋរស់នៅកកកុញទីនោះ។ អ្នកសង្កេតការណ៍យល់ថាថៃហាក់បីដូចជាចំលងការអភិវឌ្ឍន៍នេះពីវៀតណាមដែលតាមរយះសន្ធិសញ្ញាខុសច្បាប់ជាមួយមនុស្សមានអំណាចរបស់ខ្លួនក្នុងកំឡុងពេលខ្លួនឈ្លានពានកាន់កាប់ខ្មែរទាំងស្រុងរវាង១៩៧៩ដល់១៩៩៩ ហេីយបន្តអភិវឌ្ឍន៍កោះនេះរហូតមកដល់សព្វថ្ងៃ។ សម្រាប់ថៃគឺគ្មានសន្ធិក្រៅច្បាប់ណាក្រៅពីកិច្ចព្រមព្រៀងយោគយល់គ្នា MOU ចុះហត្ថលេខាឆ្នាំ២០០១។

ការប្រកាសរកស៊ីនេះជាការមិនអាចទទួលបានសម្រាប់ផលប្រយោជន៍កម្ពុជាពីព្រោះថៃអាចឆ្លាតក្នុងការបន្តអភិវឌ្ឍន៍និងលួួងលោមមន្ត្រីពុករលួយខ្មែរសម្រាប់ការបន្តគ្រប់គ្រងនាពេលបច្ចុប្បន្នទោះដឹងខ្លួនថាខ្លួនរំលោភបំពានដែនសមុទ្រខ្មែរការពារដោយច្បាប់អន្តរជាតិក៏ដោយ។ ពីឪពុកដល់កូន នាយករដ្ឋមន្ត្រីទាំងប្រកាន់គោលនយោបាយបង្រ្កាបជនជាតិខ្មែរខ្លួនឯងក្នុងការដោះស្រាយបញ្ហាព្រំដែនទាំងដីគោកនិងដីសមុទ្រជាមួយទាំងវៀតណាមនិងថៃ។ ជាតឹកតាងមានសកម្មជននិងយុវជនខ្មែរជាច្រេីនត្រូវបានចាប់ដាក់គុកនិងបង្ខំចិត្តរស់និរទេសខ្លួននៅក្រៅប្រទេស។ ថ្មីៗនេះ អតីតនាយករដ្ឋមន្ត្រីឪថ្លែងថា “ការប្តឹងរឿងកោះគុជទៅតុលាការអន្តរជាតិជាការបង្កសង្គ្រាមរវាងខ្មែរថៃ” នៅពេលដែលមេដឹកនាំថៃប្រកាសជាសាធារណះមុនហ្នឹងបន្តិច ហេីយនាយករដ្ឋមន្ត្រីកូននិយាយមិនមានជំហរច្បាស់លាស់ថា “មានតែមេដឹកនាំបក្សជំទាស់ថៃទេដែលទាមទារចង់បានកោះគុជទាំងស្រុង ដូច្នេះរដ្ឋាភិបាលខ្មែរមិនចាំបាច់ឆ្លេីយតបឬធ្វេីតាមក្រុមប្រឆាំងជ្រុលនិយមខ្មែរមួយចំនួននោះទេ” ដែលពាក្យពេជ្រមេដឹកនាំកំពូលបែបនេះគឺមិនខុសពីជាន់ករខ្មែរគ្នាឯងរួចហុចដងដាវអោយសត្រូវនោះ។

បេីយេីងសិក្សាលំអិត កម្ពុជាមានសិទ្ធិគ្រប់គ្រាន់ក្នុងការកាន់កាប់ភាគខ្លះនៃកោះគុជនិងដែនសមុទ្រធំល្វឹងល្វេីយគ្រប់ដណ្តប់កោះត្រល់ទាំងស្រុងផងដែរ។

ឆន្ទះនយោបាយនិងអនាគត

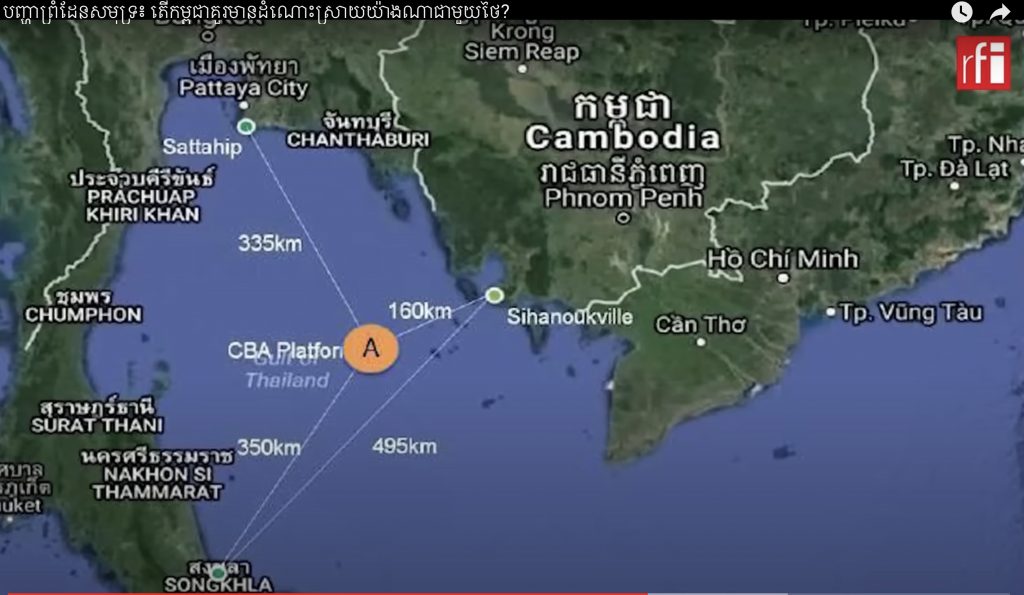

កម្ពុជាមានកំលាំងពលរដ្ឋ សេដ្ឋកិច្ច យោធា និងនយោបាយខ្សោយជាងថៃខ្លាំងណាស់ តែកម្ពុជាមានអំណាចផ្លូវច្បាប់ក្នុងដៃដែលត្រូវរួមគ្នាអនុវត្តន៍

- ១. ប្រកាន់ខ្ជាប់សន្ធិសញ្ញាបារាំងសៀម

- ២. ប្រកាន់ខ្ជាប់សន្ធិសញ្ញាសន្តិភាពទីក្រុងប៉ារីស

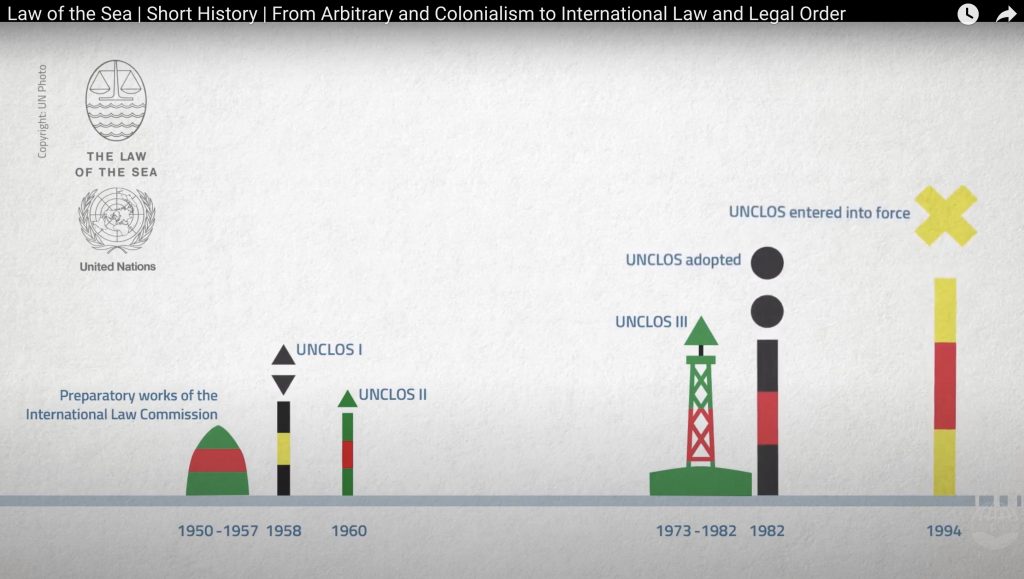

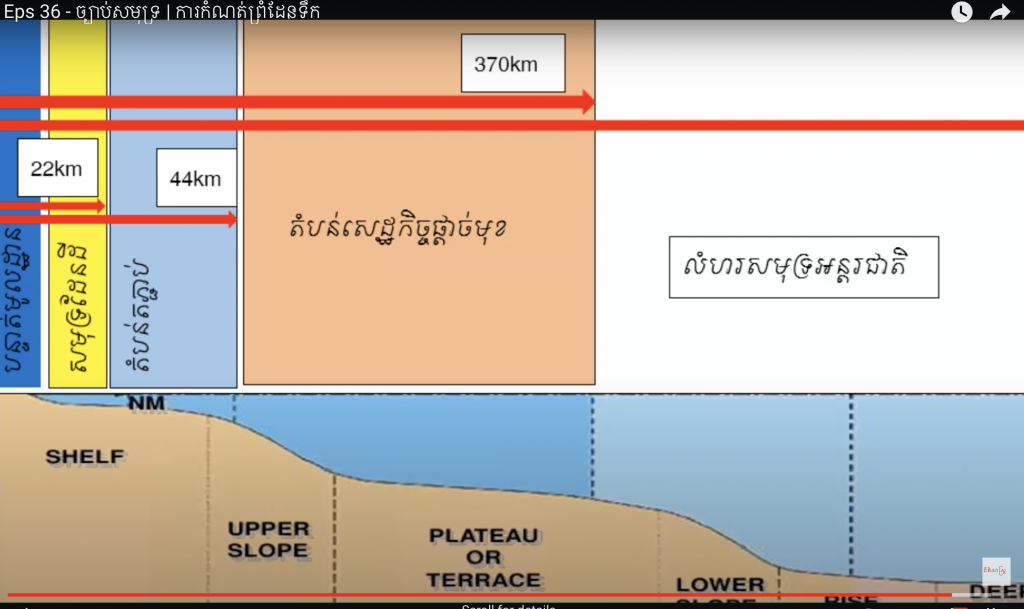

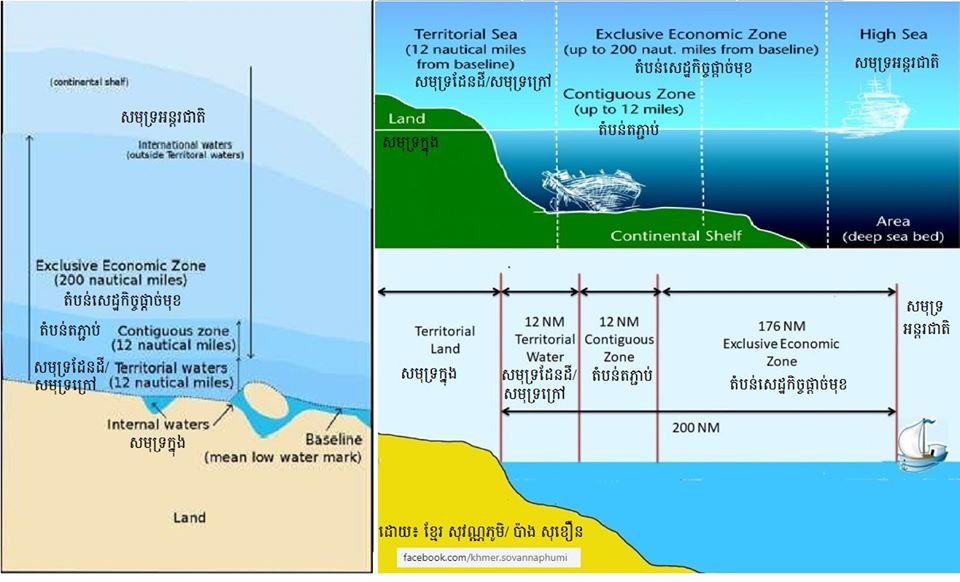

- ៣. ប្រកាន់ខ្ជាប់នូវច្បាប់សមុទ្រជាអន្តរជាតិអនុមត្តិដោយប្រទេសប្រជាធិបតេយ្យច្រេីនដាច់ខាត តែប្រទេសយក្សកុម្មុយនីសដូចជាចិន(នៅសមុទ្រចិន)និងរុស្ស៊ី មិនព្រមអនុវត្តន៍តាម

- ៤. តំកល់ទុក MoU មួយឡែកសិន ដោយលេីកយករឿងការកំណត់ព្រំដែនសមុទ្រជាមួយថៃជាមុនអោយបានច្បាស់លាស់សិន(នេះជាឳកាសល្អបំផុតដេីម្បីលេីកមកនិយាយ)

- ៥. ត្រូវប្តឹងទៅតុលាការអន្តរជាតិទាមទារសិទ្ធិកាន់កាប់តាមច្បាប់កំណត់តែប៉ុណ្ណោះ

- ៦. បញ្ឈប់គំរាម កំចាត់ និង កំចាយ សំលែងខ្មែរណាក៏ដោយដែលបារម្មណ៍រឿងបូរណភាពដែនដីរបស់ខ្លួន