Op-Ed: Khmer Times

How the nation became a graveyard for democracy

In two months, three presidents of political parties in Cambodia have been arrested and detained. May Titthara speaks to US-based academic Ear Sophal.

KT: Could you please give an overview of the current situation in Cambodia politics?

Mr Sophal: I think we’re back to square one or close to it. Twenty-five years after UNTAC and it looks like game over. UNTAC lost. The last vestige of western political liberalism has been extinguished from Cambodia. Rest in peace, democracy in Cambodia. It was a nice one-generation ride.

KT: What do you think about the arrest of Kem Sokha?

Mr Sophal: It’s terrible. I guess it means the authorities are going all the way with respect to destroying Cambodian democracy. For them, 25 years is enough. One generation. The end. After 2013 and 2017, it became clear that no matter what was done to the opposition, it only got stronger by gaining votes, so the answer became let’s just decapitate the opposition. We’ve exiled its former leader, now we’ll jail its current leader on some “smoking gun” treason charge. Well, it’s not clear his supporters will consider that to be credible stuff. They’ve known that tricks like this have been used since 1995. Back then it was a voice recording about an attempt on someone with an antique rifle.

KT: As you know, the accusation goes back a long time and has just been revived. What do you think is behind the Kem Sokha arrest?

Mr Sophal: It’s like old wine in a new bottle. You can always come up with some crazy reason. I remember back in 1995, it was Prince Sirivudh and an antique rifle and alleged murder plot that was audio recorded. It’s always the same tricks.

KT: Why has Mr Sokha been arrested at this time?

Mr Sophal: Because someone needs to show Cambodia who is boss. It’s time to crush the opposition in that person’s view. In Cambodia, might makes right.

KT: Do you think Mr Sokha’s arrest is an application of the law or a political trick? And why?

Mr Sophal: It’s not the rule of law. More precisely it’s the rule of man.

KT: If he is found guilty, what is the future of the CNRP?

Mr Sophal: Bleak. One leader was exiled and had to resign. The other was arrested and will no doubt soon be convicted of treason in a show trial. The CNRP will remain alive, like Funcinpec remained alive after July 1997. When your leader is exiled or arrested, how can you operate?

KT: What does such an arrest mean for the ruling party?

Mr Sophal: What it means is getting rid of the ruling party’s biggest domestic enemy. The charismatic leader of the CNRP has been put away under lock and key. Hooray, the ruling party can sleep at night. Or can it? Won’t this infuriate his supporters? They’ve now made a political prisoner out of him. Will Kem Sokha be Cambodia’s Nelson Mandela? If anything happens to him, he’ll be the martyr and the Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino of Cambodia.

KT: Is it fair enough for opposition parties who have no power to take revenge?

Mr Sophal: Not sure what kind of revenge they can enact. It’s not as if they have guns. They come to a fight bringing loudspeakers when the other side has guns. Might makes right in Cambodia. In love and politics all is fair. The only way to ensure victory for the ruling party is to eliminate the CNRP completely before the July 2018 election. The opposition party, even hollowed out, might be able to get votes, and that would be a huge embarrassment if they somehow won despite being decapitated.

KT: How will this affect civil society sentiment?

Mr Sophal: Civil society is already in a funk from all the beatings it has received — metaphorically and sometimes literally — and this is going to further depress them. Civil society’s main allies, The Cambodia Daily, Radio Free Asia, Voice of America, Voice of Democracy, National Democratic Institute, etc., are under assault so they probably feel like someone’s punched them in the gut. Civil society is the soul of Cambodia. Without civil society the country is morally bankrupt. It will be like Year Zero again. In any case, who is next? The Phnom Penh Post allegedly has received visits from the tax man, and I know for a

fact that Transparency International Cambodia has too. Is Khmer Times too free-thinking? Time to go to a re-education camp.

KT: Do you think the upcoming election will be free and fair?

Mr Sophal: No, it will not be free and fair. They’ve never been except for 1993. They are already the un-freest and un-fairest, if such words even exist, of all. You cannot have a skating competition where your boyfriend hires a goon to go and club the ankle of your opponent, as happened in 1994 to figure skater Nancy Kerrigan. It’s just not right, not fair, and not a free competition.

KT: In what way can we rescue such a bad situation in politics right now?

Mr Sophal: Release Kem Sokha, permit the return of Sam Rainsy to politics without conditions, withdraw the $6 million bogus tax bill to the Cambodia Daily (I mean, why not $60 million or $600 million or for that matter $6 billion?). Who doesn’t know the Daily has run at a loss for years and years and its foreign reporters get paid $1,000 a month since the 1990s. This is less than a high official spends on cognac and ladies of the night at an average dinner these days. Stop harassing NDI, RFA, VOA, VOD, and all the radio stations broadcasting them. Expelling the messenger does not solve the problems people face. The problems are still there. They don’t go away because no one is reporting on them. They will still be there tomorrow, next week, next month, and next year, when the election takes place, and even after the elections have come and gone. These are big problems that will take everyone’s imagination and ingenuity to solve, including the opposition’s.

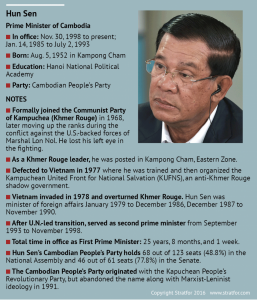

The crackdown in Cambodia is taking the form of criminalisation of the opposition and the media by Prime Minister Hun Sen ahead of the 2018 national elections. This slide into political regression is particularly troubling, as the country is still recovering from the memory of the genocide at the hands of the Khmer Rouge in the 1970s. Cambodia has enjoyed relative prosperity in recent years thanks to the boom in garment exports and tourism; it can ill-afford political unrest. Its democracy too is a work in progress, and while the long-ruling Hun Sen has never been an ideal democrat, in recent years his autocratic tendencies have become increasingly more pronounced. The

The crackdown in Cambodia is taking the form of criminalisation of the opposition and the media by Prime Minister Hun Sen ahead of the 2018 national elections. This slide into political regression is particularly troubling, as the country is still recovering from the memory of the genocide at the hands of the Khmer Rouge in the 1970s. Cambodia has enjoyed relative prosperity in recent years thanks to the boom in garment exports and tourism; it can ill-afford political unrest. Its democracy too is a work in progress, and while the long-ruling Hun Sen has never been an ideal democrat, in recent years his autocratic tendencies have become increasingly more pronounced. The