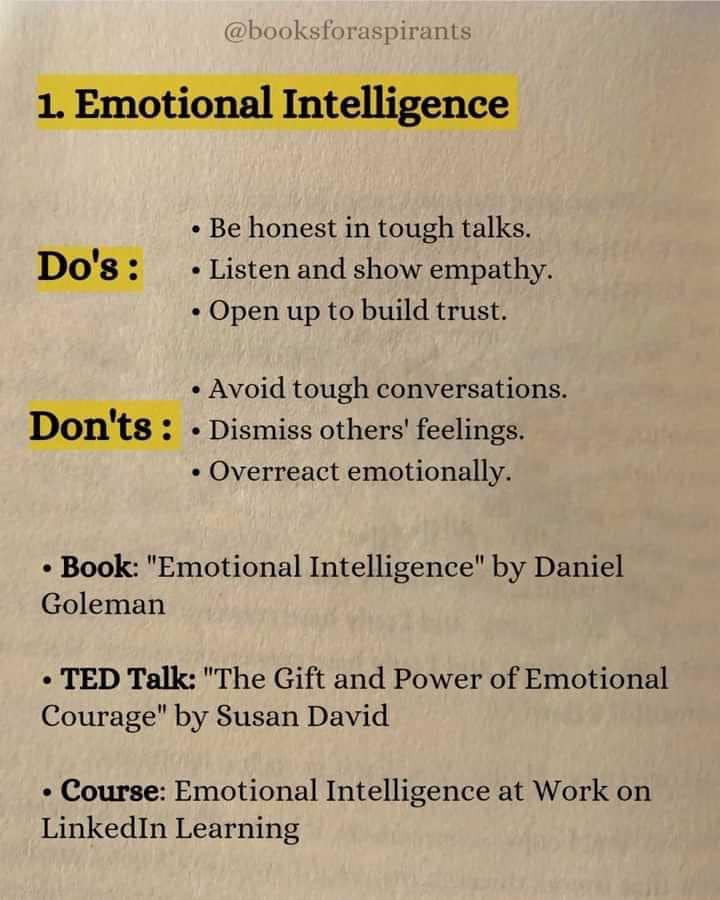

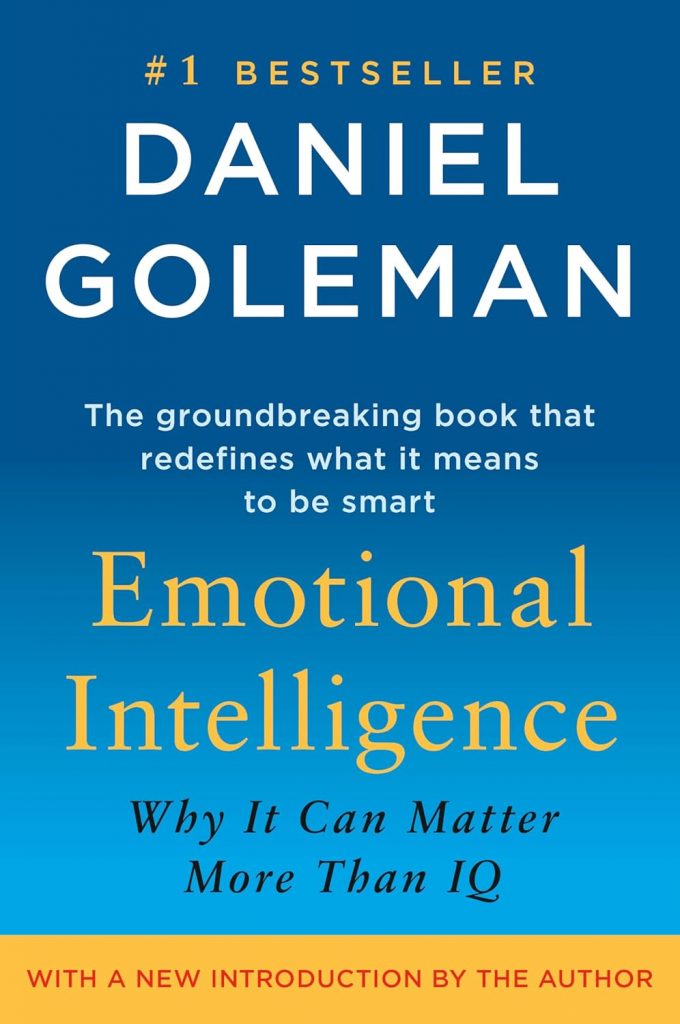

Book : “Emotional Intelligence” by Daniel Goleman

Course Level 1: Emotional Intelligence at Work on LinkedIn Learning

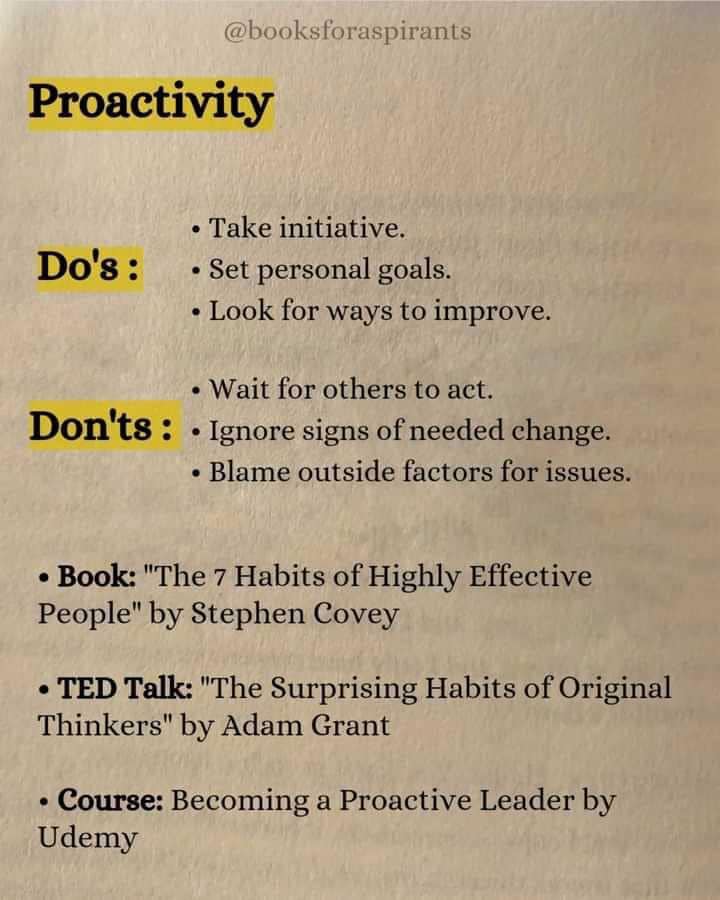

Course: Becoming a Proactive Leader by Udemy

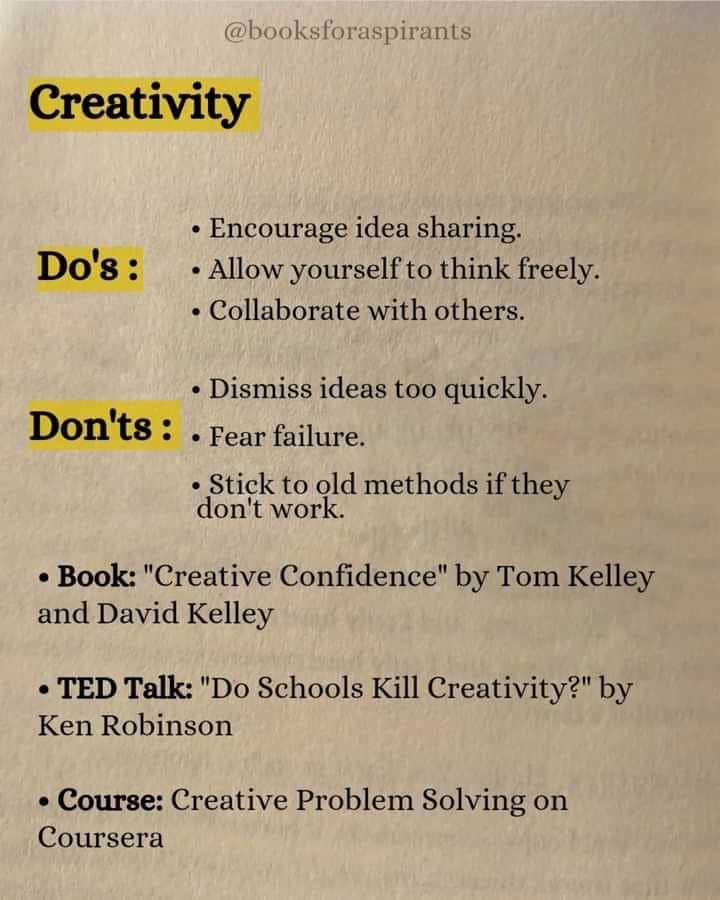

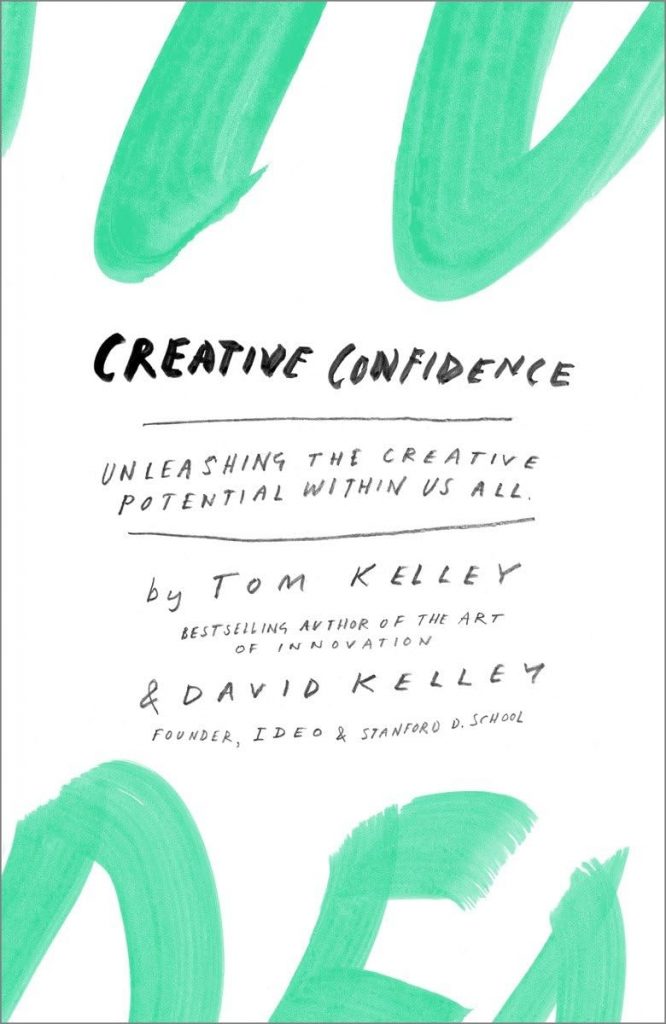

Creative Problem Solving on Coursera

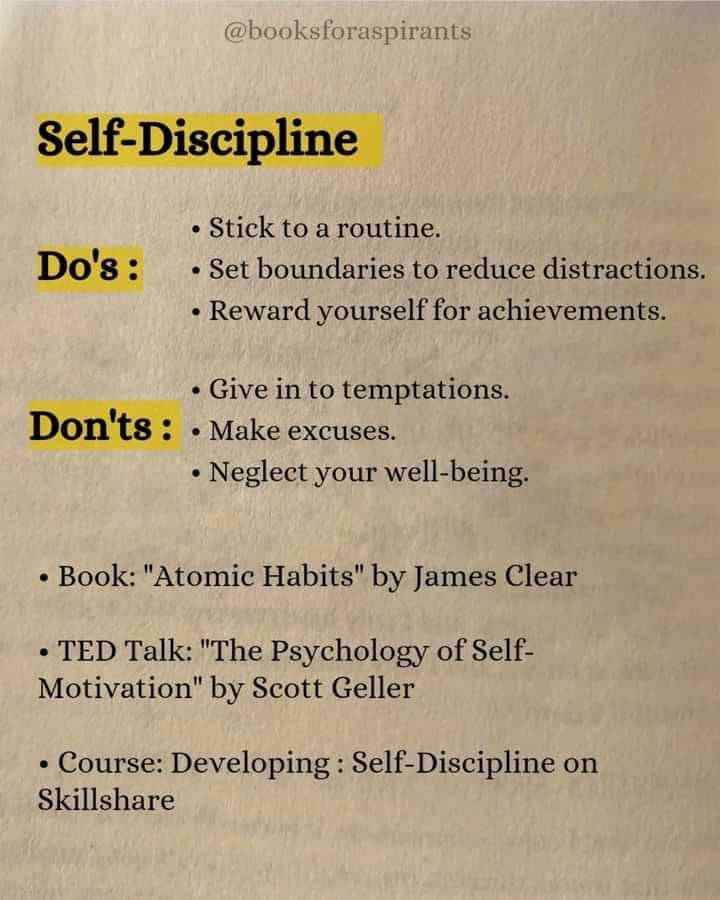

Book: “Atomic Habits” by James Clear

Course: Developing of Self-Discipline on SkillShare