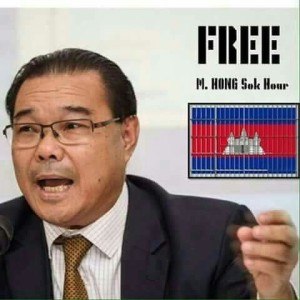

Cambodia: Drop Case Against Opposition Senator

Forgery and Incitement Charges Without Basis,

(New York) – Cambodian authorities should end the prosecution of an opposition senator who has been wrongfully charged with forgery and incitement for posting online an inaccurate version of a 1979 Cambodia-Vietnam treaty, Human Rights Watch said today. The next hearing in the case against Senator Hong Sok Hour is scheduled for October 2.

Hong Sok Hour, a dual Cambodian-French citizen who represents the Sam Rainsy Party (SRP) in the Senate, was arrested on August 15 on public orders from Prime Minister Hun Sen. He ordered Sok Hour’s arrest after he posted a video clip on the Facebook page of Sam Rainsy, president of the main opposition Cambodia National Rescue Party, of which SRP is a founding party. The authorities denied Sok Hour bail, and he is being held pending trial. The judge in the case has refused to allow him to receive a specialist medical examination and possibly necessary treatment for hypertension and cardiac disease.

“Relations between Cambodia and Vietnam are politically sensitive, but they are no excuse for bringing criminal charges over a disputed document,” said Brad Adams, Asia director. “The Cambodian government has already pointed out that the document was inaccurate and in a democracy the matter should be left at that.”

There is no basis for forgery and incitement charges, which should be dropped and Hong Sok Hour immediately and unconditionally released.

The video at the center of the case contained a Khmer-language text purporting to be article 4 of the February 18, 1979 Treaty of Friendship between Cambodia and Vietnam, which was made public at the time. Shortly after the video was posted, a secretary of state at the Council of Ministers declared the version it presented of article 4 was “fake.” In ordering Hong Sok Hour’s arrest, Hun Sen characterized the posting of the video as an “act of treason.”