February, 2019

now browsing by month

Why Hun Sen needs China now more than ever

Why Hun Sen needs China now more than ever

Pending US and EU sanctions threaten to sink Cambodia’s economy. Will China come to the rescue?

Op-Ed: Asia Time

By DAVID HUTT, PHNOM PENH

In multiple and mounting ways, from aid to trade to diplomatic protection, China keeps its geopolitical ally Cambodia afloat. That patron-client relationship was on full display late last month when Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen made a hat-in-hand four-day state visit to Beijing.

The leader came away with what he sought: More money, more promises and more comradely assurances. Beijing reportedly pledged to provide Cambodia with US$588 million in aid over the next three years, to import 400,000 tons of rice, increase bilateral trade from $5.7 billion last year to $10 billion in 2023, and broadly more investment.

“At present, China-Cambodia relations are facing new development opportunities,” China state-media outlet Xinhua quoted President Xi Jinping as saying after his meeting with Hun Sen last week. Hun Sen, for his part, wrote in a post-visit Facebook post that Xi “praised [China’s] special cooperation with Cambodia and vowed to make the relationship even stronger” and that its future development assistance for that country will be “twice more solid.”

China’s patronage is arguably more important now than ever, as the United States (US) moves to sanction Hun Sen’s regime and the European Union (EU) looks to withdraw the country from its duty-free Everything But Arms (EBA) trade scheme. Both are punitive responses to Cambodia’s recent democratic retreat, exemplified by the dissolution of country’s main opposition party in November 2017, a move that drove many of its members into exile.

Hun Sen’s ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) thus won all the seats in the National Assembly at last July’s general election, a result many Western observers and governments saw as rigged and illegitimate. The CPP has claimed that any Western criticism of its rule is an assault on the country’s sovereignty and insult to its independence, claims the long-ruling party has played up to nationalistic effect.

China, it seems, is now backing that anti-Western narrative. Its new ambassador to Cambodia, Wang Wentian, recently asserted that Western nations want to “attack the cooperation between Cambodia and China.” Geopolitical shifts partly explain why Beijing has appeared to indulge the Cambodian government’s worst anti-democratic instincts and move to a de facto one-party state after years of Western-favored multi-party democracy.

Elections last year in Pakistan, Maldives and Malaysia all saw skeptics of China’s $1 trillion infrastructure-building Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) rise to democratic power. Other regional countries have also started to air misgivings or stalled on BRI-related projects. While some reports of BRI downsides and debt traps have been exaggerated, there is a rising regional backlash against Chinese investments that are perceived to erode nations’ sovereignty and finances.

Xi stressed at a high-level symposium to mark the BRI’s fifth anniversary held in Beijing last August that its projects aim to “improve the global governance system” and build a world “community of shared destiny.” It’s a message China aims in particular for neighboring Southeast Asia, where big BRI plans for connecting infrastructure to promote and facilitate more regional trade are on the drawing board.

Read More …Is Cambodia’s Foreign Policy Heading in the Right Direction?

Is Cambodia’s Foreign Policy Heading in the Right Direction?

Cambodia needs to recalibrate its relationships with the US and EU, or risk becoming overly reliant on China.

Op-Ed: The Diplomat

By Kimkong Heng, February 08, 2019

Cambodia’s foreign policy has seen remarkable improvements after 1993 when the country held its UN-organized national election. The Cambodian government’s efforts to integrate Cambodia into the region and the world have resulted in Cambodia’s membership in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in 1999 and the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2004. The Kingdom has overall had good relations with its neighbors and other countries in Southeast Asia and beyond.

However, as a small state Cambodia has limited strategic space to maneuver and its foreign policy dynamics face considerable challenges. The country is seen to lean toward China, its closest ally and its largest economic and military benefactor, at the expense of good relations with other countries. Cambodia’s close embrace of China has become more evident since 2012. From blocking ASEAN joint statements to supporting Beijing’s One China policy, Cambodia continues to demonstrate its willingness to embrace China. In turn, China has reciprocated through increasing “no strings attached” aid and loans to Cambodia.

Both countries upgraded their relations to a comprehensive strategic partnership in 2010, and as of now China is Cambodia’s largest foreign direct investor. The trade volume between the two countries was valued at $5.8 billion in 2017, by which time China had given approximately $4.2 billion to Cambodia in the form of aid and soft loans.

While Cambodia is seen to enjoy its reciprocal relationship with the world’s second largest economy, its relations with the West look set to deteriorate.

Following the dissolution of the opposition Cambodian National Rescue Party (CNRP) in 2017 and the controversial national election in 2018, which saw the ruling party sweep all seats in the National Assembly, Cambodia’s ties with the United States reached a new low. The United States has imposed visa sanctions on high-ranking Cambodian government officials, withdrawn aid commitments, and further imposed financial sanctions, including asset freezes on the commander of Prime Minister Hun Sen’s bodyguard unit. The Cambodian ruling elites have condemned these sanctions and have repeatedly made reference to the U.S. bombing of Cambodia during the Vietnam War, rhetoric Hun Sen’s government has often used to criticize the US.

Cambodia’s ties with the European Union now also face challenges. The EU has begun the internal process to withdraw its Everything But Arms (EBA) trade preferences from Cambodia, a move the European bloc initiated in response to the Cambodia government’s perceived lack of commitment to improve its human, labor, and political rights situation. In return, Cambodia issued a communiqué calling the EU trade threat an extreme injustice. The EU has been also accused of using double standards in its treatment of Cambodia. Further, Prime Minister Hun Sen has recently warned that he would put an end to the opposition party if the EU withdraws the EBA from Cambodia.

Cambodia’s foreign policy toward the United States and the EU, analyzed in terms of recent developments, appears not to be heading in the right direction. It is not wise for Cambodia, as a small developing country, to fight against or alienate itself from the world’s largest economy and the world’s largest trading bloc. Although the Cambodian government may have strong support from China, its current approach toward the United States and the EU will not be helpful in the long run. It is certainly better to have friends on both sides of the world, rather than adopt a one-sided orientation toward friendship and foreign policy.

Hun Sen and his ruling elites’ powerful narratives of war, peace, development, poverty reduction, independence, and sovereignty are well developed and seem to be well received by many Cambodians who have first- or even second-hand experience of the atrocities of the Khmer Rouge. Most Cambodians, if not all, would not like to experience or hear about war or social instability again at all. However, they also expect more from their country and leaders. In addition to peace and stability, they have a strong desire for better opportunities, freedom, and human rights. They want to see many social issues being addressed. While they are hopeful for the future of Cambodia, they may also be worried about a possible worst-case scenario where their country may fall victim to a new cold war in Southeast Asia. Specifically, it is conceivable that Cambodia may become an object of strategies used by China and the United States in their competition for dominance in the international system and in Southeast Asia in particular.

Cambodia’s close alignment with China, although important for Cambodia’s economic development and the ruling elites’ legitimacy, does not seem to bring about sustainable and inclusive development for all. Chinese investment, aid, and loans are generally directed at the government and the Cambodian elites. Unlike the Chinese way, the Western approach to aid, loans, and investment projects is usually channelled through non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and aimed at benefiting ordinary Cambodians. Although the number and amount of aid and development projects from the West are few, when compared with a large and increasing number of the Chinese investment projects, they are usually seen to promote accountability, sustainability, and inclusiveness. Chinese investment projects, however, tend to lack transparency and accountability, leading to many environmental and social issues in Cambodia. Thus, the impact of China’s development projects on the sustainable development of Cambodia is still an open question.

Read More …Leadership indicators for the 21st Century

Table 2: Framework on transversal competencies to inform NQF Source:

Courtesy: Facebook page of UNESCO-ASIA

UNESCO (2016). Assessment of Transversal Competencies: Policy and Practice in the Asia-Pacific Region.

Domains Examples of key skills, competencies, values and attitudes

- Critical and innovative thinking: Creativity, entrepreneurship, resourcefulness, application skills, reflective thinking, reasoned decision-making.

- Interpersonal skills: Communication skills, organizational skills, teamwork, collaboration,sociability, collegiality, empathy, compassion.

- Intrapersonal skills: Self-discipline, ability to learn independently, flexibility and adaptability, self-awareness, perseverance, self-motivation,compassion, integrity, self-respect.

- Global citizenship: Awareness, tolerance, openess, responsibility, respect for diversity, ethical understanding, intercultural understanding, ability to resolve conflicts, democratic participation, conflict resolution, respect for the environment, national identity, sense of belonging.

- Media and information literacy: Ability to obtain and analyse information through ICT, ability to critically evaluate information and media content, ethical use of ICT.

- Other (physical health,religious values): Appreciation of healthy lifestyle, respect for religious values

Read more details of this Publication by the UNESCO at SDG-NQF (Sustainable Development Goal-National Qualification Frameworks)

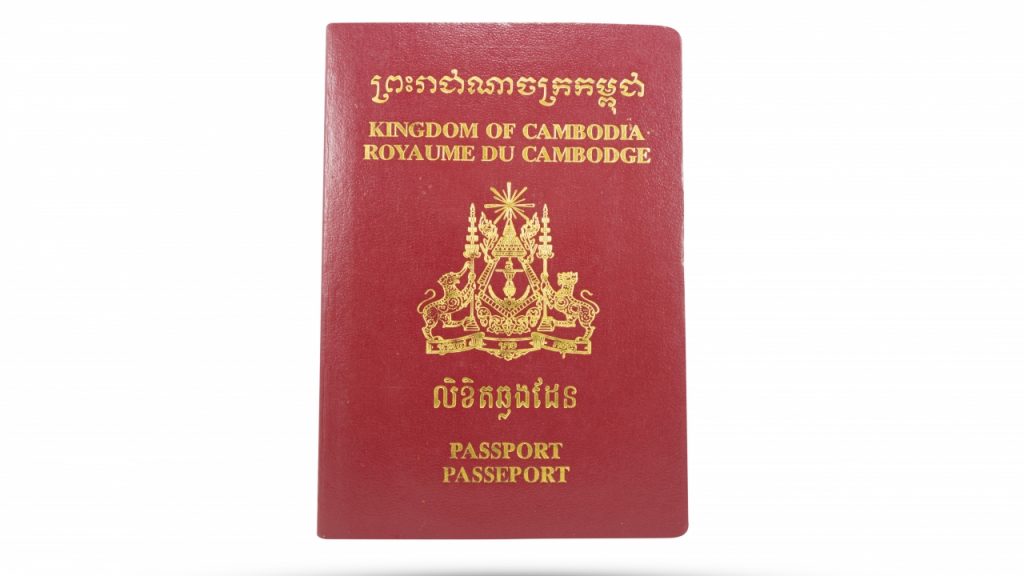

WHO GAVE THAILAND’S EX-PM YINGLUCK SHINAWATRA A CAMBODIAN PASSPORT?

- Officials insist Thailand’s former leader Yingluck Shinawatra hasn’t been given a Cambodian passport

- So how she used one to register a company in Hong Kong is a mystery that points to the ‘highest levels’, observers say

Op-Ed: South China Morning Post (SCMP)

BY PHILA SIUJOHN POWER 26 JAN 2019

Thailand’s former prime minister Yingluck Shinawatra. Photo: AFP

The news that Thailand’s former prime minister Yingluck Shinawatra is in possession of a Cambodian passport poses a troubling question for many of her new-found compatriots: who gave it to her? The self-exiled leader, who fled Thailand in August 2017 before being sentenced to prison on what she says are politically motivated charges, used a Cambodian passport to register as the sole director of a Hong Kong company incorporated in August last year – as revealed by the South China Morning Post.

Source SCMP

The red passport emblazoned with the words “Kingdom of Cambodia” in gold might not be what anyone would expect Yingluck Shinawatra, former prime minister of Thailand, to present at an immigration checkpoint.

With visa-free or visa-on-arrival access to just 54 destinations worldwide, it is ranked among the least powerful passports in the world by the annual Henley Passport Index, at a lowly No. 84 out of 104.

Officially, anyone with US$300,000 to spare can pick up a Cambodian passport. That is what Cambodia requests as an investment before handing out its travel document.

Yingluck, in self-exile since 2017, before Thailand’s supreme court sentenced her to five years in prison for mishandling rice subsidies, used a Cambodian passport to register herself as sole director of a Hong Kong company incorporated last August last year, according to official filings. The disclosure, in a South China Morning Post story this month, added to the theory that she fled Thailand via Cambodia.

It also put the spotlight on the ease with which the world’s wealthy can obtain new passports or residency in a new country if they have the cash it takes – anything between US$100,000 and US$2 million.

This can all be above board and properly regulated, with thorough screening of applicants. In some cases, however, getting a new passport has been said to be as easy as shopping online, and the individual does not even have to show up in person.

Some get new passports by bribing officials.

“For some investors, they want to move to somewhere else because they truly want to do business there,” said Benny Cheung Ka-hei, director of the Goldmax Immigration Consulting in Hong Kong. “But then of course, some of the rich Chinese have too much money to spare and have no problems spending a few million dollars on foreign passports. They want foreign passports as protection, and also for showing off.”

But Phnom Penh has denied that Yingluck holds a Cambodian passport and observers question whether there has been a royal decree conferring citizenship on her – something that is required of all other foreigners.

Cambodia denies it issued a passport to former Thai prime minister

Mu Sochua, vice-president of the banned Cambodia National Rescue Party, said she did not believe Cambodian officials’ claims they were not aware of Yingluck’s Cambodian passport.

“There are many, many issues in terms of legality and sovereignty as far as Cambodia is concerned … where is the royal decree? No citizenship can be issued without a royal decree, and to get a passport from any country, you need to be a citizen of that country,” said Sochua, who fled her own country in 2017.

Mu Sochua, vice-president of the Cambodia National Rescue Party. Photo: Reuters

Sochua demanded Cambodia’s strongman Prime Minister Hun Sen investigate.

“Isn’t he concerned that an ex-prime minister holds a passport of his country? And if he has not ordered it, then who has? Who ordered the passport to be issued?

“For Yingluck, an ex-minister of Thailand, I don’t think an official at the Ministry of Interior or the Foreign Ministry would dare to [issue it] – even if she wanted to buy it for a million dollars.”

Sochua believes Yingluck received the passport because of her ties with Hun Sen. Yingluck’s brother, Thaksin Shinawatra, also a former prime minister of Thailand in self-imposed exile, used to be an adviser to the Cambodian government.

Cambodia launches crackdown on passports

“The Thai junta government has collaborated with the Hun Sen regime in deporting Cambodian political asylum seekers to Cambodia. The question is: will the Thai junta ask Hun Sen to seek the deportation of Yingluck if and when she travels with the Cambodian passport?” added Sochua.

Sophal Ear, associate professor of diplomacy and world affairs at the Occidental College in Los Angeles, said the decision to grant Yingluck a passport must have come from “the highest levels” of the Cambodian government.

Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen. Photo: AP

Read More …